Cinema as a Tool for Human Rights Protection: An Interview with Swiss Documentarian Stefan Ziegler

Stefan Ziegler, a recognized director and university lecturer, visited Bishkek to showcase his film "Mandate — For Whom International Law Matters" at the "Bir Duyno" human rights film festival in early December. His work was awarded a prize presented by the festival organizer Tolekan Ismailova and the chairman of the Union of Cinematographers of Kyrgyzstan Talaybek Kulmendeev.

Ziegler attracted attention due to his unique combination of creativity and human rights issues; his films have significantly influenced documentary cinema. At the meeting, he said: "You know, I am not a tourist in your country, but I am here to discover it for myself anyway."

- How did you start your journey in cinema, and what inspired you to work in this field? Which films or directors have influenced you the most? You also work in international law; how do you combine cinema and law?

- In fact, I am not a professional filmmaker and did not study film at university. I don't have time to watch films, but I have always felt like a creative person. Art has been an integral part of my life, and I see myself more as an educator and advocate for humanitarian interests than as an ambitious "filmmaker."

I perceive filmmaking as a means of conveying important information. Having worked in the humanitarian field for 25 years and being in conflict zones, I realized that cinema can be a powerful tool. When I founded my film company Advocacy Productions, it reflected my mission. It may sound strange, but I draw my greatest inspiration from two sources.

The first is the works of German playwright Bertolt Brecht, who emphasizes the importance of critical thinking. His approach taught me to use narrative to tell stories in a way that allows viewers to focus on the essence of what is happening. In the film "Mandate," I even played the role of the main character, and this technique turned out to be interesting for the audience.

The second source of inspiration is the PAR (Participative Action Research) methodology, which places the people we work with at the center of the research. We learn from them and adapt our films according to their opinions, which allows us to "give voice to the voiceless." This applies not only to cinema but also to the academic community as a whole. In the academic environment, people are often viewed rather than understood, which allows for the creation of films for youth that take their perspectives into account.

That is why the film "Broken" has been viewed by over 3 million people, including thousands of teenagers over the age of 14. They understand what is happening better than we can imagine. I plan to create the next documentary about international law for young people.

- Can you draw parallels between your films "Broken" and "The Mandate" and the issues that exist, for example, in Kyrgyzstan, in our society?

- Both films and other educational materials of mine are dedicated to international law, which is relevant for all countries. It is not just an intellectual concept but also an ethical question. We intuitively understand what can and cannot be done.

For example, we all agree that killing an unarmed civilian is unacceptable. We understand the importance of protecting those who are not involved in the conflict for establishing peace after the war.

These ideas are based on the Geneva Conventions and international humanitarian law, which, together with human rights and refugee rights, make up what we call international law, recognized by the community of states.

In my films, I strive to convey to viewers the idea of how we understand the law in conflict situations, as this can happen to any of us at any moment. If we can appeal to a common understanding of laws that are difficult to apply in practice, we can use that same understanding for peaceful living.

This logic has been well received by audiences in your country. I am glad that young people in universities and at the film festival actively discuss these issues and are ready to engage in discussions.

Kyrgyzstan can be proud of its active youth, who critically reflect on what is happening.

- What brought you to Kyrgyzstan? How did you first learn about Kyrgyz cinema and the culture of this country?

- I had the honor of being invited by the embassies of Switzerland in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan. They organized a two-week tour for me with film screenings and lectures.

Switzerland is known for its neutrality and for upholding the Geneva Conventions, which form the basis of modern international humanitarian law.

The government of my country supports the opportunity to show and discuss my films in Kyrgyzstan and many other places where this may be difficult.

During the two weeks, I gave lectures three to four times a day, followed by interesting discussions, half of which took place in universities, a quarter with media representatives, including filmmakers and artists, and the remaining time I spent with civil society organizations. Although my stay was short, interacting with many people gave me insight into the authentic culture.

- What are your goals regarding international law during your visit here? What is the main objective of your tour?

- My goal is to show my film at the "Bir Duyno" festival. The audience's reaction to the film helps me better understand what needs to be done. A month ago, when I was here, I noticed how open people are to new ideas and how they react to my film.

I was invited to gain a deeper understanding of their views and interpretations of international law. This willingness to learn inspires me as a filmmaker and educator.

At one of the meetings, I was surprised when asked if I wanted to show the film at the festival. This highlights the directness of the Kyrgyz people and surprised me.

I am convinced that the five Central Asian countries can significantly strengthen their positions if they work together in a spirit of solidarity. International law can become one of those unifying forces.

This requires the exchange of ideas and experiences, and if we can do this through cinema, engaging both academic circles and ordinary people, we can formulate a common viewpoint. I would like to help create a discursive educational center based on reflections on international law through the lens of cinema.

If my experience inspires more active engagement based on participation and learning, it can lead to positive changes in society.

- You talk about alliances. Are there like-minded individuals in Central Asia working in the field of international law and cinema who are interested in something more than just being viewers?

- Yes, but it is not easy. There are few filmmakers among them; rather, they are intellectuals and advocates for those whose voices are less heard.

It is important not only to have directors but also people with good hearts who can convey important messages through films or educational processes. I cannot do this alone — an alliance of those who care about youth and share my vision is necessary.

These joint efforts represent a true mission that needs to be communicated to people from within, rather than from academic circles meant only for the elite.

- Tell us about your upcoming project that you mentioned earlier. What message do you want to convey, and what details can you reveal?

- The film I am preparing will be called "Curious," and its duration will be about five and a half hours. It is an educational material for teachers that can be used in full or in parts. It will be adapted to various geographical regions, and people will be able to choose what suits them.

The material is suitable for use in different settings — it can be applied throughout the semester or in weekend seminars.

If someone works at a university, for example, with architects, they will be able to select specific sections that are appropriate for their discipline.

It took eight years to create the material. We had many teachers from 20 countries who engaged youth and asked for their opinions on what they understood or did not understand.

Young people from these countries shared their reflections on international law, representing a microcosm of various ideas.

The film "Curious" is planned to be released in the next six months.

The International Court of Justice and the International Criminal Court are located in The Hague, and we hope that the Dutch government will allocate funds to support the rule of law to make the film available for free to everyone, especially teachers.

In the first phase, we will translate subtitles into Kyrgyz, Russian, and over 30 other languages to make them accessible to a wide audience.

- You primarily deal with international law. How was the process of filming and editing your documentary? Did you discover anything new while working on it?

- When we were working on our first film "BROKEN — A Palestinian Journey Through International Law," we changed the title to make it more appealing. It is now called "BROKEN PROMISES — Israel, Palestine, and Justice: Arguments for International Law."

This reflects our desire to reach as many people as possible with the film.

We did not plan to make other films, but I became interested in the candid testimonies of judges from the International Court about their work and memories. We used archival materials that had not been used in cinema before.

I felt the need to complete what I had started, and six years later, I released the film "Mandate," which was shown here a few days ago. Our films are very different from each other; they are genuine documentary works that are part of the educational process and transcend temporal boundaries.

Our films interest a wide range of people: from lawyers to youth and ordinary citizens.

Four weeks after the release of "Mandate," we received a request from the library of the International Court for digital copies of our film. How they found out about us remains a mystery, but it was pleasant.

At one of the meetings with the former president of the court, I handed her a copy of "Broken," and she replied that they use our film for their training.

This was a great surprise for me.

- Do you have any plans for the future or film projects that you are looking forward to?

- Tomorrow, I have a meeting with a local artist whose works have been exhibited abroad and who speaks in a unique way. I saw a film about him and could only read the subtitles in Kyrgyz.

I thought it was impossible for the subtitles to be created by an ordinary translator — it was too poetic. I am going to confirm this with the well-known translator Zina Karayeva. If my suspicions are confirmed, we will shoot a documentary featuring this artist titled "Poetry and International Law – An Artistic Understanding of Conflict Law."

I have about 12 projects in the archive waiting to be realized. I am inspired by the Kyrgyz people and strive to return to this amazing land once again.

Read also:

On December 30, the national film award ceremony "Ak Ilbirs" will take place in Bishkek.

On December 30th at 17:00, the National Film Award "Ak Ilbirs" ceremony will take place...

Who won the main film award of Kyrgyzstan "Ak Ilbirs" in 2025? List

The award ceremony of the XII National Film Prize "Ak Ilbirs" took place on December 30...

The "Ak Ilbirs" Film Award Ceremony Will Take Place in Bishkek

The award ceremony of the National Film Prize "Ak Ilbirs" will take place on December 30,...

The international documentary film festival on human rights took place in the Kyrgyz Republic.

From December 12 to 16, 2025, the XIX International Documentary Film Festival on Human Rights...

Azerbaijani film to be screened at a prestigious international film festival

At the 24th International Film Festival, which will take place from January 10 to 18, 2026, in...

On December 30, the National Film Award "AK Ilbirs" ceremony will take place in Bishkek.

The winners will be determined in 12 nominations At the ceremonial event, which will take place at...

Film Award "Ak Ilbirs". The film "Kachkyn" has been recognized as the Best Film.

The awards ceremony of the national film prize "Ak Ilbirs" took place the day before in...

The film "Kurak" has been included in the official program of the film festival in Mumbai.

The Third Eye Asian Film Festival, taking place in Mumbai, India, has included the film...

Theater and film actress Vera Alentova has passed away.

She was 83 years old...

Who Gets the Grand Prix? Results of the Documentary Film Festival on Human Rights Announced

The XIX International Documentary Film Festival took place in Bishkek, organized by the NGO...

Scholarships and Awards: Successes of Students in Studies and Sports Celebrated at the Kyrgyz-Uzbek International University

At the Batyraly Sydykov Kyrgyz-Uzbek International University, a solemn ceremony was held to...

"Work, Brothers!" Kyrgyzstan Takes Third Place at the International Police Film Festival

The festival recognized the achievements of law enforcement officers At the international...

"Kyrgyzstan will have its own film studio and its own Dolby Atmos studio, - Minister of Culture"

The film industry in Kyrgyzstan is actively developing today: about 70% of distribution...

The Head of the KR stated the need to revive the Kyrgyz film industry

At the meeting of the People's Kurultai, the President of Kyrgyzstan, Sadyr Japarov,...

A monument to the film director Tölömüş Okeeva was unveiled in Bishkek

On October 30, a ceremony was held in Bishkek to unveil a monument to the outstanding film...

A New Year's Tree for Children with Disabilities Took Place at the Puppet Theater

A festive event was held at the State Puppet Theater named after Musa Jangaziev for children with...

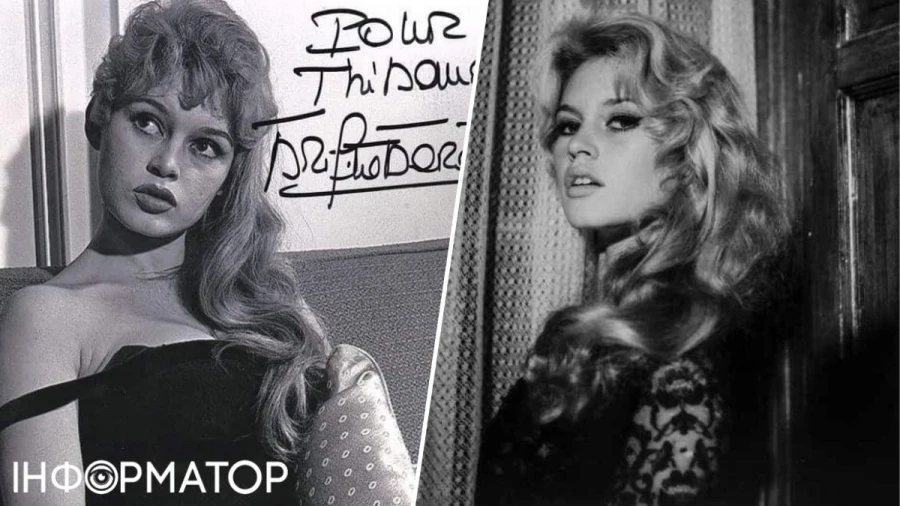

French actress Brigitte Bardot has passed away

Today it was announced that Brigitte Bardot, the famous French actress, has passed away, as...

Brigitte Bardot Has Died - Legend of French Cinema

Brigitte Bardot, the famous French actress, model, and activist, passed away at the age of 91. This...

In Bishkek, a ceremony for handing over the keys to apartments under the GIC program was held with the participation of the president.

- Today, January 12, an important ceremony took place in Bishkek, where the President of the Kyrgyz...

The Opera and Ballet Theater has received a Steinway & Sons piano worth 25 million soms.

In the Malachite Hall of the National Opera and Ballet Theater named after A. Maldybaev, a concert...

Russian actress Vera Alentova has died

Photo from the internet Famous Russian theater and film actress, People's Artist Vera...

The Opera and Ballet Theater presented the poster for January 2026

The Kyrgyz National Academic Theater of Opera and Ballet named after A. Maldybaev has announced...

Zoe Saldana Becomes the Highest-Grossing Actress in Film History

American actress Zoe Saldana has set a record, becoming the highest-grossing actress in the...

In Bishkek, the first military historical series in the history of Kyrgyzstan "Ört kechken söyke" will be presented

On December 29, the long-awaited premiere of the military historical TV series "Өрт кечкен...

A piano worth 25 million soms was handed over to the Malybaev Opera and Ballet Theater

The question of modernizing instruments has remained open since the 1980s The Malybaev Opera and...

Actress Vera Alentova Has Died

We mourn the passing of the People's Artist of Russia Vera Alentova, whose death was confirmed...

Kyrgyz ballet artists completed their tour in Spain

The ballet troupe of the Kyrgyz National Academic Theater of Opera and Ballet named after A....

The UN expressed concern over the situation in Venezuela and the detention of Maduro

On January 3, a sharp escalation of the conflict occurred: American troops struck targets in...

Hollywood-Asia: Kate Winslet: Directorial Debut "Goodbye, June" Based on a Script by Her Son. Interview with Asel Sherniyazova

Interview of Asel Sherniyazova with Kate Winslet. The film Goodbye, June marks Kate Winslet's...

The list of the most anticipated movies of 2026 has been announced

Experts in film distribution and analytics have presented a list of movies that audiences are...

In Naryn, drivers were given gifts reminding them of traffic rules

In the Naryn region, an event took place where drivers were given gifts reminding them of the...

Life in the Regions: Maksat Korchiev at 51 is Studying to Become an Actor and Dreams of Cinema

Maksat Korchiev, a 51-year-old resident of the village of Kerege-Tash in the Ak-Suu district, is...

A monument to the legendary director Tolomush Okeyev was unveiled in Bishkek

On Chuy Avenue, near the "Oktabr" cinema, a solemn opening of a monument to Tolomush...

Project "Zheneke": Nurgul Nurkalieva from At-Bashy wanted to become a theater and film actress, but everything changed after meeting a guy.

The regional news outlet Turmush continues the column "Жеңеке" (Zheneke). In it, we share...

An Evening in Memory of the Artist Chingiz Aydarov Will Take Place in Bishkek

On the evening of January 24, an event in memory of the artist Chingiz Aydarov will take place at...

"Great Triumph". The artists of the opera and ballet theater have returned from their tour in Spain.

The tour of Kyrgyz artists in Spain turned out to be a true triumph, as reported in a press release...

A Kyrgyzstani's flag was taken away at the entrance to the stadium in Saudi Arabia, where the match between Barcelona and Athletic took place.

Adilet Kerimbek uulu from Kyrgyzstan shared his experience of attending a football match in Saudi...

In the city of Shopokov, a single mother and a mother of many children were awarded certificates for 100,000 soms.

In Shopokov, a ceremony was held to present social contract certificates, which were issued to a...

"Main Thing - Sincerity!" The Story of Ernist Adylbekov - the Real Santa Claus

As the New Year approaches, Santa Claus enters his most intense period. For Ernist Adylbekov, a...

UN calls to protect children from the horrors of war in 2026

According to the United Nations, by 2025, children in conflict regions such as the Democratic...

Citizens of Kyrgyzstan Named Important Achievements and Events for the Country in 2025

A recent sociological survey conducted by the Kusein Isaev Center for Social Research at Bishkek...

The Chairman of the Union of Cinematographers of Kyrgyzstan Has Changed

Photo of the Union of Cinematographers of Kyrgyzstan. Busurman Odurakaev At the XXIX Congress of...

Bishkek's Weekly Agenda: Movie Premieres, Evening of Romances, and Classics by Candlelight

January 13-16. Permanent exhibitions at the museum The museum features permanent exhibitions of...

Ministers Meet Delegates of the IV People's Kurultai. List

In Bishkek, on December 25, the IV People's Kurultai will take place at the Toktogul...

UN Security Council held an emergency meeting on the situation in Venezuela

An emergency meeting of the UN Security Council was held to discuss the current situation in...

Legendary French actress Brigitte Bardot has died

Details are not yet disclosed Brigitte Bardot, the renowned French actress, singer, and model,...

Trump and Zelensky to Hold Talks in Florida on December 28

The meeting, announced by the White House, will begin at 3:00 PM local time. Representatives of the...

Piano for 25 million, 7 billion soms budget, demolition of cultural monuments. A large interview with the Minister of Culture Mirbek Mambetaliev.

АКИpress presents the results of 2025 in the field of culture in Kyrgyzstan, gathered from the...