Kazakhstan is striving to replicate Singapore's successful experience in creating gambling zones, but risks facing a failure similar to that of Macau, as noted by the publication "Vremya".

Cautious Investment Attraction

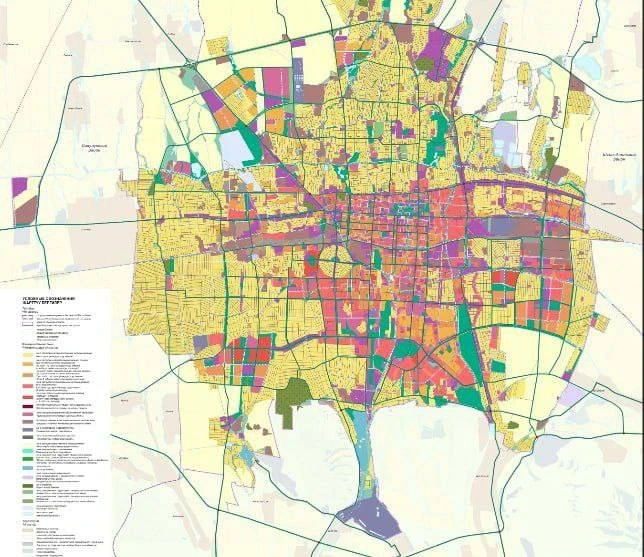

The Ministry of Tourism and Sports of Kazakhstan is actively discussing the creation of new gambling zones, which local residents will not be able to enter. The aim of this step is to attract foreign investments while minimizing the risks associated with gambling addiction within the country.

According to the ministry's press service, 46% of residents in the Mangistau region support this initiative. The ministry's forecasts suggest that by 2029, the region will welcome 148,000 foreign tourists, create 7,000 jobs, and generate tax revenues from casinos of about 1.2 billion tenge annually.

In Zhetysu, 67% of the population also approves of this project. It is expected that 36,000 tourists will visit, 700 jobs will be created, and tax revenues will reach 2.4 billion tenge per year.

The Almaty region accounts for 54.5% support. The creation of two gambling zones is planned by 2028, which should attract at least 22,810 tourists by 2030, create 2,000 jobs, and ensure tax revenues of 6.5 billion tenge.

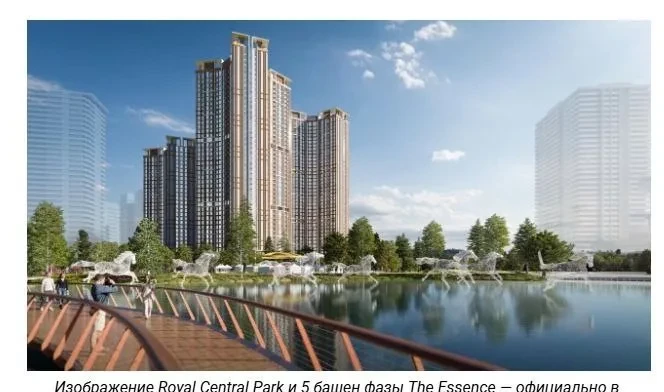

The ministry also reports that each new casino will contribute between 2 to 3 billion tenge in taxes to the budget and create about 500 jobs. Construction has already begun at "Warm Beach" in Mangistau and at the international tourist center "Ak-Bulak" in the Almaty region, thanks to private investors.

— Global practice shows that gambling zones that operate only for foreigners can help attract tourists and develop resort infrastructure without negatively impacting the internal social environment, — the ministry states.

However, the experience of neighboring CIS and Asian countries indicates that the results may not be so straightforward.

Who Wins in Gambling?

It should be noted that strict separation of gambling zones for foreigners is rare in the CIS.

The only example may be Kyrgyzstan, where casinos on Issyk-Kul and in Bishkek are initially closed to local residents. In 2025, the country's budget received a record 443 million soms (just over 5 million dollars) from them, but this concerns only a few establishments.

In Russia, all four gambling zones located in tourist areas are open to everyone. Georgia, on the other hand, has a completely different model: casinos operate throughout the country, especially in Batumi and Tbilisi, without separate zones for foreigners. However, since 2021, the authorities have imposed strict restrictions on Georgian citizens: for example, the minimum age for gambling is 25 years, and gambling is prohibited for civil servants, people with debts, and certain other categories. As a result, over 1.5 million citizens ended up on a blacklist.

Foreigners can gamble from the age of 18 and pay lower taxes — 5% on winnings, while locals are burdened with higher rates. Therefore, the gambling industry is oriented towards tourists and brings billions to the budget, but initially led to an increase in gambling addiction among the local population, forcing the Georgian authorities to take radical measures.

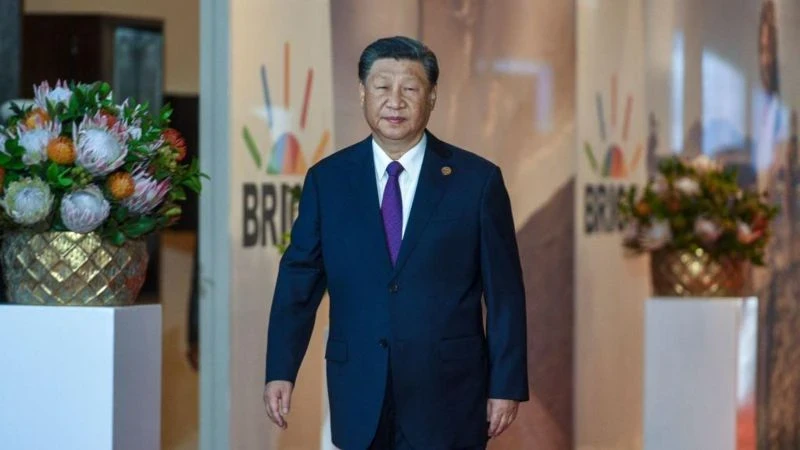

The Ministry of Tourism of Kazakhstan, in turn, refers to the experiences of Singapore and Macau as primary examples.

Let’s examine them in more detail.

Singapore introduced an entry fee for its citizens: 150 Singapore dollars per day, or 3,000 per year. As a result, the share of locals among players dropped to 2-3%. Thus, there is formally no ban on gambling, but the financial barriers proved effective.

Macau, on the contrary, opened 12 zones exclusively for foreigners in 2023 and provided operators with tax incentives of up to 5%. However, this initiative failed: foreign tourists showed no interest, and the zones remained half-empty. Ultimately, they were deemed ineffective.

Kazakhstan, according to the Ministry of Tourism, aims to attract tourists while protecting society. However, there is one significant problem: corruption risks could undermine this initiative.

The Gambling Injection

Let’s recall the unfortunate experience with the Betting Accounting Center (BAC).

From 2018 to 2020, the Ministry of Culture and Sports (later — Tourism and Sports) actively promoted the creation of the BAC, which was supposed to become a unified system for all payments and bets of bookmakers. Officially, it was presented as a way to bring a huge market (with a volume of about 600 billion tenge per year) out of the shadows, increasing tax revenues by 25-30 billion tenge and protecting players from fraud.

However, it turned out that the BAC was conceived as a monopoly structure: all bets went through one server, and the operator charged a 4% commission, which, by various estimates, brought in 20-25 billion tenge a year.

On February 22, 2021, the anti-corruption service detained the Vice Minister of Culture and Sports, Saken Musaybekov, who was removed from a flight from Nur-Sultan to Dubai at the airport. At the same time, the owner and director of the company "Exirius," chosen by the Ministry of Culture as the BAC operator, were also detained.

In August 2021, the court found Musaybekov guilty of bribery and fraud using his official position, imposing a fine of 62 million tenge.

After this scandal, the BAC project was frozen. In 2022, the Ministry of Culture officially abandoned it, calling it a "useless structure." Nevertheless, the idea was not forgotten.

In 2024-2025, it was revived under a new name — the Unified Accounting System (UAS), positioned as a state platform with a 1% commission, which could bring in 13-15 billion tenge a year.

The history of the BAC has become a classic example of how good intentions to regulate the gambling market in Kazakhstan turned into a mechanism for creating a private cash cow, which was closed only after corruption became evident.

Today, as new gambling zones and the UAS are discussed, many recall this story as a warning.

Let’s Show the Cards

Tourism consultant Yulia Palchevskaya believes that until the system is operational, it is premature to talk about corruption risks. The main question is how justified this scheme is.

— It is not entirely correct to cite Georgia and Singapore as examples, — she notes. — In Georgia, the gambling business has indeed developed, but it is geographically oriented. In Turkey, despite a developed economy, there is one of the strictest anti-gambling legislations in the world. Georgian casinos effectively operate for the Turkish client, but where does Kazakhstan plan to attract players from?

According to her, foreigners choose destinations not only based on the availability of games but also on developed tourist infrastructure and reasonable prices.

— I would like to hope that wealthy tourists will head to Kazakhstan because of the new gambling zones, — Palchevskaya remarks skeptically. — But the reality is that there are many variables in this area, which means that gambling business centers can be counted on one hand. These variables are primary for tourism development, while the choice of destinations is merely a consequence.

Aigerim Khandullaeva, a lawyer specializing in migration law, believes that creating gambling zones for foreigners is a way to quickly attract tourists and currency, but from a legal and financial standpoint, this model is extremely risky.

— This will lead to the creation of different legal regimes based on citizenship, which contradicts the principle of equality and Kazakhstan's international obligations, — she emphasizes. — Even if such restrictions are enshrined in law, they may become the subject of legal disputes, creating legal instability for businesses and investors.

Moreover, Khandullaeva notes that for foreign tourists, not only gambling is important, but also the protection of rights, transparent rules, and financial security. If a country is associated with gray schemes and sanction risks, the flow of quality tourists will not come, and instead, only problematic capital may arrive.

— The practice of other countries shows that "foreign" gambling zones quickly become environments for fictitious residencies and shadow settlements, which increases the risks of money laundering and international claims against the financial system, — she adds. — The state, striving to become a financial hub, cannot simultaneously create an image of a "casino jurisdiction" for dubious capitals, as this undermines the trust of banks and investors.

Ultimately, as Khandullaeva concludes, a short-term influx of funds may result in long-term damage to the economy and the country's image, which will prove significantly more costly than temporary benefits.

One can only assume that if the new zones in Mangistau or "Ak-Bulak" end up in the hands of "needed" investors with formal control, all optimistic forecasts about taxes and jobs will remain only on paper, and the money will end up in the pockets of intermediaries.

As a result, Kazakhstan may face not Singaporean success, but a fiasco and another corruption scandal.

Are the stakes too high?