Aeon: How the Conquest of Foreign Territories Came to Be Considered Unacceptable

Author: Cary Goettlich

In the modern world, there are fewer and fewer things that evoke consensus among people, but one of the few exceptions is respect for the "sovereignty and territorial integrity" of states. Virtually all governments recognize this principle as fundamental in international relations. The UN Charter, ratified in 1945, obliges countries to refrain from the use of force or threats against the territorial integrity and political independence of other states. In this essay, I use the term "state" to denote independent political entities, avoiding more vague concepts such as "nation" or "country."

Today, it is almost impossible to find a person who openly supports the legality of the annexation of another state's territory carried out by force. Although conquests continue to exist, they are usually hidden under other pretexts.

Modern political figures proudly refuse to recognize conquests as legitimate, creating the appearance of a civilized international order. But what can justify the violent seizure of someone else's land? The idea that conquest is unacceptable in international relations is relatively new. As the Dutch jurist Hugo Grotius argued in the 17th century, treaties that end wars must be adhered to, even if they impose unjust conditions, such as the transfer of part of a territory. These treaties, however unjust they may be, are often the only way to end a conflict, and a principled refusal to adhere to them could make the end of wars impossible. The 19th-century American lawyer Henry Wheaton also noted that most European nations acquired their territories through conquests, which were subsequently legitimized by long-term possession. From this perspective, the existence of almost any state depends on the legitimacy of conquests.

However, instead of Grotius's concept of "the rights of peoples," which sought to limit conquest, the modern international order guarantees the absolute right of each state to its territory within existing borders. It is prohibited to benefit only from conquests made after 1945, while conquests that occurred before this are considered legitimate. Thus, modern society condemns annexations, but conquests that took place in the past remain undisputed.

What factors led to the creation of an international order that so resolutely defends the status quo?

The prohibition on annexation, which has become widespread and deeply rooted, arose from a combination of many circumstances. Interestingly, states with the greatest capacity for conquest are often their fiercest opponents. It is not surprising that conquests are condemned by victims and potential victims. But what is more curious is this: why do the United States, possessing the most powerful military, actively support the ban on annexation? The U.S. is present in many regions of the world and often uses force, but since the conquest of the Northern Mariana Islands during World War II, it has not annexed new territories. Why does the world's only superpower impose limitations on itself?

The answer to this question lies in the roots of the formation of the United States: they were founded on a particular type of colonialism that sought land ownership and the use of slave labor, and later on agrarian and industrial capitalism. Until 1900, the United States did not cease its territorial expansion, making it similar to many empires in history, but its conquests were largely the result of the actions of the settlers themselves. Even before declaring independence, British authorities tried to restrain the expansion of settlers, as it led to costly wars that threatened the stability of Europe. After gaining independence, the federal government of the United States became much less committed to adhering to territorial agreements with indigenous peoples, although it could not control the chaotic movement of settlers westward.

Interestingly, many future states—such as California, Florida, Hawaii, Texas, and Vermont—had brief periods of independence before becoming part of the United States. These are just successful examples; many "quasi-states" in Appalachia, such as Vandalia and Watauga, never received official recognition.

Thus, conquest has always occupied a central place in the history of the United States, albeit not in the form characteristic of European colonial empires. While the federal government encouraged settlement, the true engine of expansion was the rapid advance of the settlers. But was this form of conquest fundamentally different from European imperialism, which the United States declared complete in the Western Hemisphere in the Monroe Doctrine? By the 1890s, settler expansion had reached Hawaii, and the creation of an overseas empire became quite real for the United States. The question of the nature of the American empire became the subject of active public debate.

The imperialism of the 1890s found itself caught between the principles of laissez-faire and liberal egalitarianism. Americans at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries debated what their imperialism should look like. This dispute is often described as a confrontation between "imperialists," such as historian A.T. Mahan, and "anti-imperialists," like William Graham Sumner. However, there was much common ground between them. For both Mahan and Sumner, Spain's conquests were unacceptable, as they contradicted the freedom and initiative that they believed were the foundations of viable nations. Sumner argued that the conquest of the Philippines was analogous to "the conquest of the United States by Spain," as colonial expansionism could poison American politics. Despite his imperialist views, Mahan believed that "colonies develop best when they grow on their own," in accordance with the nature and ambitions of the settlers.

When American settlement covered the entire continent, the next step was not obvious. As Sumner believed, the conquests of the 1890s were caught between the free market and equality. If the conquered people are "civilized," then conquest loses its meaning, as all benefits can be obtained through trade. If they are "uncivilized," then establishing power over them undermines the principle of equality.

The United States resolved this dilemma by developing a special type of imperialism based on trade and business. The new American imperialism was based on the old, not directly governed by a centralized state. Instead of farmers and settlers of the 19th century, the main agents of 20th-century expansion became businessmen and railroad magnates. Their activities abroad, American leaders believed, should contribute to prosperity within the country and reduce class conflicts.

The concept of new imperialism was articulated in the "Open Door Notes" of 1899 and 1900. The "Open Door" policy represented a diplomatic campaign by the United States against outdated European imperialism in China, paving the way for American business. In the 1899 note sent by Secretary of State John Hay to the great powers, it asserted the right of all countries to equal trading conditions in China. The second note, sent in 1900 against the backdrop of the Boxer Rebellion, proclaimed the United States' desire for peace in China, the preservation of its "territorial and administrative integrity," the protection of American rights, and the provision of "the principle of equal and impartial trade."

The United States consistently supported the Open Door policy in China in the early 20th century. In 1915, Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan stated that the U.S. would not recognize any agreements that "infringe upon the rights of the United States and its citizens in China, the political or territorial integrity of the Republic of China, or the international policy known as the Open Door policy." After World War I, this policy formed the basis of the Nine-Power Treaty of 1922, where the U.S., Great Britain, Belgium, China, France, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, and Portugal agreed to "respect the sovereignty, independence, and territorial and administrative integrity of China."

Immediately after the Spanish-American War of 1898, when the U.S. conquered the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam, American officials began to openly oppose conquests. Roosevelt's Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, which asserted the right of the U.S. to intervene in the affairs of Western Hemisphere countries to maintain order, was accompanied by assurances that "the United States does not covet land... all this country wants is to see neighboring states stable, orderly, and prosperous." In 1906, Secretary of State Elihu Root traveled to South America, asserting: "We desire no victories except victories of peace; we covet no territory except our own; we want no sovereignty except sovereignty over ourselves."

During this period, U.S. intervention in Latin America significantly increased. Under President Theodore Roosevelt (1901–1909), the U.S. controlled the Panama Canal (1903), occupied Cuba (1906–1909), and intervened in the affairs of the Dominican Republic (1904) and Honduras (1903 and 1907). However, after more than a century of territorial expansion based on purchases and conquests, the U.S. officially renounced new territorial acquisitions.

The idea of renouncing conquests is not always associated with the U.S. and its informal imperial ambitions. In recent years, analysts from leading think tanks have begun to link the principle of territorial integrity with what they call "a rules-based international order." The origins of this order are usually traced back to the establishment of the UN after World War II, when the global community sought to learn lessons from previous catastrophes and build a more peaceful order. Many researchers also point to the 1919 League of Nations Covenant as the beginning of the renunciation of conquests: Article 10 promised to "respect and preserve from external aggression the territorial integrity and existing political independence of all members of the League." What was the significance of the Open Door policy in this process?

To understand this, it is important to note that Article 10 was originally controversial and ambiguous. In the U.S., it became the main reason for the Senate's refusal to join the League of Nations: there was a risk that it would obligate the country to intervene in foreign conflicts. Canada repeatedly sought to soften or exclude this article. Why should the Canadian army be responsible for maintaining world borders, many of which could be unjust and which some peoples have the right to seek to change?

In January 1923, France invaded the Ruhr in response to Germany's failure to pay reparations, and in August of the same year, Italy seized the Greek island of Corfu after the murder of an Italian general. France feared that the League's improper intervention in the Italo-Greek conflict could draw attention to its own actions in the Ruhr. What was the significance of Article 10 in such situations?

The Permanent Advisory Commission of the League of Nations attempted—and failed—to find a more specific definition of "aggression," considering these complexities. Delegates from France, Belgium, Brazil, and Sweden argued that the old understanding of aggression as a simple crossing of borders was outdated in the context of modern warfare and proposed a more complex concept that took multiple factors into account. This, of course, would protect France from automatic blame for the occupation of the Ruhr. At the same time, Britain, fearing that its weakened military resources could become embroiled in a conflict with the U.S., effectively halted all attempts by the League to define aggression. Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald expressed it this way: any definition of aggression would become merely "a trap for the innocent and a guide for the guilty." By the late 1920s, the meaning of Article 10 remained quite uncertain.

By the 1930s, uncertainty had given way to panic. The Wall Street crash of 1929 led to a global depression, Britain abandoned the gold standard, Japan conquered Manchuria and established the puppet state of Manchukuo, and in 1933, Hitler came to power in Germany. Global conditions forced the League of Nations to seek greater clarity.

Enter U.S. Secretary of State Henry Stimson, a Harvard Law School graduate, member of the secret society Skull and Bones at Yale, and descendant of one of the Founding Fathers of the U.S., Roger Sherman. Stimson closely monitored Japan's actions in Manchuria, seeking to maintain the Open Door policy. Initially, Washington's position was similar to Britain's: both Japan and China had their arguments, and the best course of action was to seek an agreement. However, Stimson went further and concluded that Japan had crossed the line of a "responsible great power." It was not only protecting its interests around the South Manchurian Railway, as it claimed, but was also establishing political control over all of Manchuria, using bombings of cities far from the railway zone.

Failing to gain support for tough measures, Stimson took a decisive step: he sent a diplomatic note that effectively reiterated Bryan's position but with much broader implications. The U.S. refused to recognize any agreements or situations that arose in violation of the rights of the United States, including violations of the territorial and administrative integrity of China and the Open Door policy. This position became known as the Stimson Doctrine, or the doctrine of non-recognition of acquired territories. Through decisions of the League of Nations Council and Assembly, the 1933 Non-Aggression Pact, and subsequent agreements, the principle of non-recognition of conquests became a norm of international law and continues to this day.

Why did the Stimson Doctrine of 1932 become international law, while Bryan's similar note of 1915 was ignored? One reason is that Japanese aggression extended beyond Manchuria and affected Shanghai, where European powers had significant interests. But more importantly, in 1915, the U.S. was a peripheral power, whereas World War I made it a key player, eliminating many competitors. British diplomats viewed the doctrine of non-recognition with skepticism, considering it overly moralistic and alien to British tradition. However, by the early 1930s, Britain was managing a declining empire and became more vulnerable.

British Foreign Secretary Sir John Simon sought to avoid catastrophe by trying to please everyone—the U.S., the League, and Japan simultaneously. When Stimson sought collective affirmation of the principles of the Open Door, Simon found a compromise: he agreed to the League of Nations articulating the doctrine of non-recognition while avoiding sanctions. On February 16, 1932, the League Council approved a statement that included the Stimson Doctrine. All parties were relatively satisfied: Stimson received support, the League gained principle, and Japan avoided penalties.

Nevertheless, in Manchuria itself, the doctrine changed little. Moreover, the occupation of Manchuria became only a prologue to World War II—the largest war of conquests in history. It did not stop Italy from seizing Ethiopia and did not prevent Japan from further aggressions in China and the Nanjing Massacre.

Why is it important to remember that the modern prohibition on conquests is largely a product of informal American imperialism? One answer lies in the shift in U.S. foreign policy under Donald Trump. In 2019, the U.S. was the first to recognize Israel's de facto annexation of the Golan Heights.

Rhetoric matters, especially when accompanied by concrete actions. However, the significance of changes in U.S. policy also depends on the reactions of other countries. The prohibition on conquests has never been an exclusively American project: it has been based on the interests of the majority of countries seeking to avoid seizure.

The principle of territorial integrity is complex. In Woodrow Wilson's interpretation, it meant a prohibition on annexation but not armed intervention. This narrow interpretation re-emerged during the U.S. and allied invasion of Iraq in 2003, when respect for territorial integrity meant maintaining borders but not renouncing military control.

Today, such a narrow interpretation is being criticized in light of recent annexations. Conquest remains illegal, but its moral significance may weaken. International orders come and go. There was once an order in which conquest was regulated but not prohibited. A new order will inevitably arise—and it is increasingly unlikely that attitudes toward conquests will be shaped by the ideological constructs of the U.S.

Original: Aeon

Read also:

Sadyr Japarov announced tough measures against corrupt judges

At the recent People's Kurultai, President Sadyr Japarov noted that dissatisfaction with the...

Jokes Forbidden: Yet Another Controversial "Amendment" Passed by Kazakhstan Senators

According to the new amendments adopted by Kazakh senators in the area of crime prevention, the...

Sadyr Japarov spoke about how Kyrgyzstan is achieving energy independence

At the recent People's Kurultai, the President of Kyrgyzstan, Sadyr Japarov, emphasized the...

Over the last 70 years, the area of glaciers in Kyrgyzstan has decreased by 16 percent

At the recent People's Kurultai, President Sadyr Japarov emphasized that Kyrgyzstan,...

"Such a crime cannot be justified": Kamchybek Tashiev made a harsh statement regarding the murder of a Bishkek resident

The head of the State Committee for National Security expressed his feelings about the terrible...

The President of the Kyrgyz Republic promised to provide significant concessions to businesses.

At the People's Kurultai, the President of Kyrgyzstan, Sadyr Japarov, announced plans to...

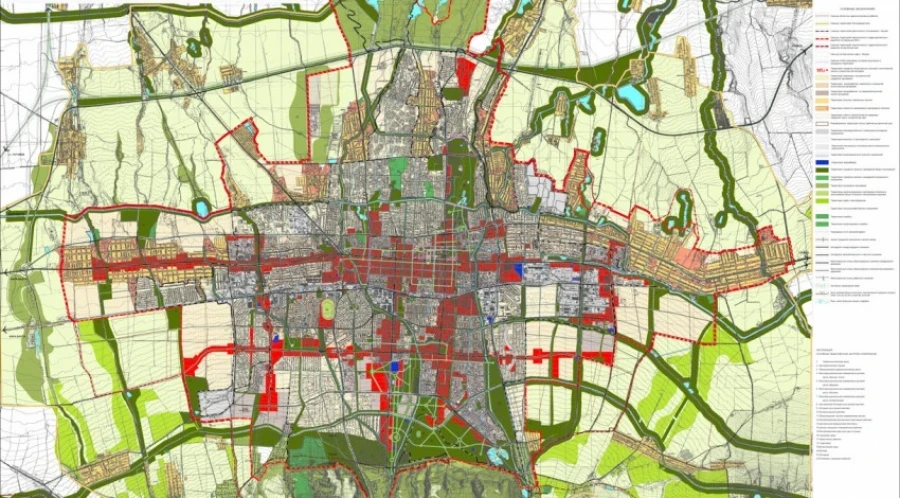

A Bishkek Resident Was Surprised – Private Property Became State Property According to the New Master Plan

About 300 houses changed ownership A resident of Bishkek, Roza Bektashova, was shocked to learn...

Trump stated that the US "must definitely" acquire Greenland after appointing a special envoy

Louisiana Governor Jeff Landry has been appointed as the U.S. special envoy to Greenland by...

Non-Combat and Unrecognized: Suicides in the Ukrainian Army That Are Silent

This is a translation of an article from the Ukrainian service of the BBC. The original is...

Zelensky spoke about the 20 points of the peace plan. What's new in it?

President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelensky presented a draft agreement for ending the war, which was...

Trump gifted Tokayev a key to the White House and a baseball cap

The American president left his autograph on the baseball cap Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, the president...

Sadyr Japarov: Those who embezzled state property stole our future as well

President Sadyr Japarov stated at the People's Kurultai that Kyrgyzstan is actively...

In the musculoskeletal system of children, there are specific features that make it possible to not recognize a fracture immediately, - traumatologist

Traumatologist and Deputy Head of the Department of Pediatric Surgery at KSMU, Arthur Satylganov,...

The Head of the KR stated the need to revive the Kyrgyz film industry

At the meeting of the People's Kurultai, the President of Kyrgyzstan, Sadyr Japarov,...

Sadyr Japarov spoke at the IV People's Kurultai (text of the speech)

Today, December 25, the President of Kyrgyzstan, Sadyr Japarov, addressed the people, the deputies...

Sadyr Japarov: Salaries of teachers and doctors will double from April 1

President of Kyrgyzstan Sadyr Japarov announced a significant increase in salaries for social...

How to Celebrate New Year Without Becoming Trauma Patients - RCUZ

At the Republican Center for Health Promotion and Mass Communication, recommendations were shared...

Violation of Consumer Rights in Online Trade Will Become a Priority Topic in the EAEU

The Eurasian Economic Commission has approved the theme "At Home on the Internet: Know Your...

In the school in the village of Novoe, children learn "from each other," with only 30 cm between the board and the desk. If the Minister of Education has no gasoline, she can take bus number 18 and see for herself, - delegate

In the village of Novoe, located near Kuntuu, there is a school named after Kaparov, which was...

Pirates Copied Entire Spotify: 300 TB of Music Leaked Online

According to Anna’s Archive, their project is a "repository for preserving music," which...

In 2025, more than 4,600 families received mortgage apartments from GIK, - Sadyr Japarov

- In 2025, we achieved historic results in providing housing for our citizens. This was reported...

Crisis Can Become an Opportunity. Kyrgyz Tailors are Seeking New Markets

Problems with the export of textile products to Russia have become a serious lesson for Kyrgyz...

The head of the Kyrgyz Republic announced comprehensive modernization of the education sector

Education is one of the key foundations for building a state and developing human capital. This was...

The Ministry of Labor of the Kyrgyz Republic clarified the policy on attracting foreign labor.

Amid public discussions regarding the attraction of foreign labor and the presence of foreign...

Putin Does Not Plan to Attack Europe, Says Director of U.S. National Intelligence

Gabbard also noted that the "war instigators" from the deep state, as well as their...

In Russia, a cleanup of the market from questionable imports has begun: the import of toys from Kyrgyzstan is banned.

In Russia, an active cleanup of questionable imports has begun, which has manifested in the...

China is concerned that AI threatens the power of the Communist Party and is trying to rein it in

Chatbots pose a particular threat, as their ability to generate their own responses may encourage...

Sadyr Japarov: We are simplifying investment procedures and eliminating administrative barriers

- We are eliminating administrative barriers and simplifying the investment process. This was...

UNESCO warns of a serious decline in the level of freedom of expression and journalist safety worldwide

According to the report "Global Trends in Freedom of Expression and the Development of Media...

Who Gets the Grand Prix? Results of the Documentary Film Festival on Human Rights Announced

The XIX International Documentary Film Festival took place in Bishkek, organized by the NGO...

Russia is approaching the status of an old country, with over a million pensioners by 2030

In Kyrgyzstan, there are currently 815 thousand pensioners registered. This was reported by...

"From April 1, 2026, the salaries of doctors and teachers will increase once again by 100%," - Sadyr Japarov

President Sadyr Japarov, during the fourth People's Kurultai held on December 25, noted that...

The issue of electric scooters in Kazakhstan has once again reached the level of parliament.

The topic of electric scooter usage in Kazakhstan has once again attracted the attention of...

"Either build a hydroelectric power station or return the land," - a delegate of the Kurultai on businessman Rakhatebek Irsaliyev

- In Chon-Kemin, Rakhatebek Irsaliev, a private businessman, plans to build a small hydropower...

Touching New Year Greetings from ANO "Eurasia": Volunteers Visited Veterans of the Great Patriotic War

In the run-up to the New Year, activists and volunteers from the ANO "Eurasia" organized...

New Hypothesis: Consciousness Generates the Quantum Field of the Universe

Joachim Kepler, a researcher from the DIWISS institute in Germany, has proposed a theory that...

The Minister of Labor discussed migration issues with representatives of Kyrgyz diasporas - delegates of the People's Kurultai.

The Minister of Labor, Social Protection, and Migration Kanat Sagynbaev held a meeting with...

Fatty cheeses and creams are associated with a lower risk of dementia

According to a conducted study, participants who consumed at least two slices of fatty cheese...

An American startup plans to release 50,000 soldier androids in two years.

The Phantom MK-1 robot, which was recently unveiled, is currently generating a lot of discussion....

The Speaker of the Parliament of Kyrgyzstan spoke at the IV People's Kurultai. What did he talk about?

During his speech, Nurlanbek Turgunbek uulu discussed the work of the new VIII convocation of the...

Lukashenko called Putin a "wolfhound" in politics

In a recent interview with the American television channel Newsmax TV, Alexander Lukashenko, the...

Pavel Durov is Fighting Global Infertility — and He Already Has 100 Children of His Own

According to the clinic, many of the female patients seeking services looked wonderful and were...

What is happening with Donald Trump's health?

Recent appearances by the president and his schedule have sparked numerous rumors, possibly partly...

Canadian Company Sues Kazakhstan Again Over Uranium

World Wide Minerals Ltd has initiated a review of the arbitration case, as reported by Orda.kz....

At the Kurultai, the issue of abuse in places of detention was raised

At the recent People's Kurultai in Bishkek, delegate Aysalkyn Karabaeva raised an important...

Not the Same Love: What Emotions Our Ancestors Experienced

Scientific research shows that emotions are not universal and can vary greatly depending on...

Sadyr Japarov: The Era of Unpunished Predatory Enrichment Has Ended

At the fourth People's Kurultai, held on December 25, 2025, the President of Kyrgyzstan,...

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Kyrgyz Republic: A New Legal Regime for Foreigners Introduced in Russia

This concerns migrants without legal grounds for staying in the Russian Federation Starting from...