Russian and Ukrainian Drone Manufacturers Buy Components from the Same Chinese Companies

According to The Financial Times, Russian and Ukrainian drone manufacturers are using the same Chinese companies to procure components.

Chinese manufacturers are doing everything possible to avoid simultaneous appearances of Russian and Ukrainian customers at their factories.

The publication notes that both sides often receive the latest parts almost simultaneously. "We can spot a new video transmitter on Russian drones and immediately understand which Chinese company manufactured it," shares Alexey Babenko from the Ukrainian company Vyriy Drone. "We reach out to them, and of course, at first they refuse: 'No, this is not ours.' But upon a second request, they say: 'Okay, we can sell this to you too.'

According to him, a similar process works in reverse: "We ask them to make something for us, and within a week they send samples to Russia, and then start producing the same for them."

Drones have become a key and rapidly evolving weapon in the protracted war, accounting for three-quarters of recent losses. Both countries have begun to ramp up their production capabilities, relying on Chinese components.

As a result, their armies have become dependent on the same Chinese suppliers. These suppliers provide processors, cameras, and motors that determine the flight range of drones and the quality of their "vision," with the cost of these components being about a third of the prices of Western analogs.

Thousands of kilometers from the front, the supply chains of Russia and Ukraine intersect in faceless office skyscrapers and industrial zones of Guangdong and Shenzhen. Here, companies producing small parts that support military drones are trying to organize the process so that representatives of opposing sides do not cross paths on the same territory.

Technological innovations reach both sides almost simultaneously. "We can see a new video transmitter on Russian drones and immediately understand which company produced it," adds Alexey Babenko from Vyriy Drone. "We write to them. At first, they respond: 'No, this is not ours.' But we reach out again, and they agree: 'Alright, we can sell this to you too.'

According to him, this principle works in the opposite direction as well: "When we ask them to make something for us, within a week they send samples to Russia and start producing the same for them."

For Yakovenko, this creates a bitter irony. At the front, engineers from TAF Industries often face shortages of parts, while their opponents, on the other side of the trenches, appear significantly better supplied with Chinese technology.

Officially, China maintains a neutral position in the conflict and has banned the export of sensitive technologies to both Russia and Ukraine. Nevertheless, Western intelligence data and Ukrainian politicians claim that Chinese authorities are "tilting the scales," allowing wealthier Russian companies to acquire entire production lines to relocate to Russia—despite Western sanctions and export restrictions from China.

While Ukraine strives for the localization of drone production, according to Yakovenko, it still relies on China for 85% of components for simple FPV drones, which are controlled via remote cameras and often used for kamikaze attacks.

According to data from the analytical company Drone Industry Insights, China produces 70-80% of all commercial drones in the world and controls the production of key components—speed controllers, sensors, cameras, and propellers.

“This clearly demonstrates how much control China actually has over the outcome of this war,” notes Katarina Buchatsky from the Kyiv military analytical center Snake Island Institute.

“They could simply decide whether to supply Ukraine or not. Currently, drones are a key weapon on the battlefield. This underscores how influential China has become,” she adds.

The Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated that the country "has always adhered to an objective and fair position on the Ukrainian crisis" and "has never supplied lethal weapons to either side of the conflict," as well as "strictly controls the export of dual-use goods, including drones."

While Moscow and Washington negotiate a difficult ceasefire, the outcome of hostilities is increasingly determined not on the front lines, but in the exhibition halls of Guangdong and Zhejiang, in WeChat chats, and over glasses of baijiu in hotel bars.

“This is madness,” says Buchatsky. “We have a hot war going on right at the border, while on another continent both sides are in the same group chat, where some Chinese factory writes: 'The Russians pay more. Sorry, come back next year.'”

At one of the largest drone exhibitions in the world, held last year in Shenzhen, Chinese companies freely interacted with buyers from Eastern Europe. Booths offering everything from ready-made drones to motors, cameras, software, and even a robotic "dog" with weapons filled the vast Shenzhen Convention and Exhibition Center.

Among more than 800 exhibitors of industrial and civilian equipment, several companies showcased flying devices with mock-ups of guns or missiles. Despite the formally commercial nature of the exhibition, many sellers and buyers admitted that their primary clients were military structures.

A Russian engineer, who wished to remain anonymous, reported that he was searching for components—flight controllers, radio channels, thermal imaging cameras, as well as intelligent control systems. He was part of a large purchasing group in matching black polos and added that the delivery of such devices from China is "not easy," but "we have our channels," refusing to elaborate on the details. "The whole world hates us," he said, referring to the numerous restrictions on drone supplies to Russia.

At the booth of one infrared camera manufacturer, the director stated that his company does not sell products directly to foreign markets. When asked about the flow of Russian-speaking visitors, he explained that external sales are conducted through trading companies. "This is quite a sensitive issue," he added, declining to disclose details.

At another drone exhibition in Shenzhen, held in late September on the industrial outskirts of the city, an employee of a Chinese components supplier reported that some drones are delivered to Russia by truck through Kazakhstan, adding that customs checks there are infrequent.

Beijing restricts the export of so-called dual-use goods—including a wide range of drones and their components—and has repeatedly tightened these rules since the beginning of the war in Ukraine. In September 2024, China introduced export controls on a number of products necessary for the production of combat drones, including flight controllers, carbon frames, motors, radio modules, and navigation cameras.

However, Zhao Yan, a representative of the state-owned company Shanxi Xitou UAV Intelligent Manufacturing, acknowledges that due to the versatility of drones and the multitude of intermediaries, it is often difficult to identify the end user and the purpose of the product.

“We can only inform you what you want to install on the drone and what lift it should provide, and if that meets the technical requirements, then that is sufficient,” he says. “If the buyer is an ordinary user who then modifies the device, that is already beyond our control.”

Other exporters complain that previous workarounds, such as shipping drones in disassembled form for local assembly, have become less effective. Some large companies claim to be well acquainted with customs procedures and obtain export licenses without problems, while smaller firms increasingly turn to expensive third-party logistics operators using complex routes.

On the first day of one of the Shenzhen exhibitions, Financial Times journalists were approached three times by card distributors offering delivery of "sensitive cargo," including drones. A representative of Shunfayi International Logistics later confirmed that the company has "over 20 years of experience transporting batteries and drones to Russia" and that various models of fixed-wing drones shown in photographs can still be delivered to the country.

Chinese components continue to be found in downed Russian drones. Last year, the Ukrainian armed forces published photographs of a two-stroke engine with an intact serial number found on a intercepted Gerbera drone. The manufacturer was identified as Mile Haoxiang Technology from Yunnan province, although experts emphasize that the presence of Chinese parts alone does not prove the intent to supply to Russia.

They also point out that Russian drones regularly contain components from various countries. An analysis by the Kyiv Center for Defense Reforms showed that in 2025, Chinese components slightly outpaced American ones, while Swiss components ranked third.

The company Mile Haoxiang Technology did not respond to a request for comment.

Evelyn Buchatsky, managing partner of the Ukrainian venture fund D3, which invests in defense startups, notes that both sides are successfully circumventing export restrictions by creating, for example, intermediary structures in Germany or Poland.

“There are many loopholes. Ultimately, export control has only slightly increased friction in the supply chain but has not interrupted it,” she says.

Buchatsky also adds that Russia is actively engaged in "relocating" Chinese production: "They are buying entire supply chains, and since they are always willing to pay more, we find ourselves at the end of the queue."

Alexey Babenko from Vyriy Drone recalls a call from a Chinese factory, where he was informed that he could now buy any number of motors that were previously unavailable. The reason, as explained, was that the Russians decided to purchase an entire production line rather than individual components and no longer needed the motors that were previously reserved for them.

Vladimir Zelensky also claimed that Chinese companies operate directly in Russia. "There are production lines in Russia where Chinese representatives are present," he noted.

Zelensky and other Ukrainian officials have repeatedly stated that the Chinese government helps Russia import drone technologies by selectively applying its export restrictions.

“We used to rely on Chinese Mavic drones. Now their sale to Ukraine is blocked, but remains open to Russia,” Zelensky said in May last year. “Now our forces produce drones independently.”

According to Babenko, Ukraine has made "significant progress" in localizing production but still depends on China for key components and is vulnerable to export restrictions, complex supply routes, and political pressure.

Yakovenko adds that even if relocating Chinese production lines were possible, they would immediately become targets for Russian strikes.

Russia, relying on the close personal relationship between Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping, has deepened economic integration with China and uses state resources to ensure a more stable flow of components, including entire supply chains.

“Chinese equipment, materials, and components allow Russia to deploy so-called 'local' production of engines while remaining effectively dependent on the Chinese technological and raw material base,” says Alexander Danilyuk from the Center for Defense Reforms.

The production of Geran and Garpiya drones, based on Iranian developments and used for long-range strikes on Ukrainian cities, has significantly increased: the number of launches rose from dozens per month in 2022 to over 5,000 per month by November.

In October 2024, the U.S. Department of the Treasury imposed sanctions on two Chinese companies—Xiamen Limbach Aircraft Engine Co and Redlepus Vector Industry Shenzhen Co—for supplying Russia with components for the production of the Garpiya drone.

The same sanctions package included the Izhevsk Electromechanical Plant "Kupol"—a subsidiary of the state corporation "Almaz-Antey"—as well as the trading company TSK Vektor, which, according to the U.S. Treasury, "served as an intermediary between the plant and Chinese suppliers in the Garpiya project." The Izhevsk plant, according to the agency, "coordinated the production of the Garpiya series at enterprises in China, after which the drones were transferred to Russia."

The U.S. Treasury reported that this trade was financed through regional clearing platforms that facilitated payments for sanctioned goods, and that in January 2025, sanctions were imposed on 15 such platforms.

Particular attention from experts was drawn to one cross-border deal that, according to analysts, would have been difficult to execute without the approval of Chinese authorities. In November, the Financial Times reported that a businessman from Shenzhen, Wang Dinghua, owns a 5% stake in Rustakt, the manufacturer of the VT-40 drone widely used by Russia. Companies Shenzhen Minghuaxin and other entities owned by Wang were major suppliers of components for Rustakt.

Other Western officials claim that the Chinese state directly assisted Chinese sellers and Russian buyers in circumventing Western sanctions and export controls.

“We have information that a state-linked Chinese company helped a Russian defense firm circumvent Chinese export restrictions by using a Central Asian country as a formal end user,” sources said.

The names of the company and the country were not disclosed. The January sanctions from the U.S. Treasury mention the Kyrgyz Keremet Bank as an operator of a regional clearing platform. The bank did not respond to a request for comment.

“After the U.S. Treasury released information about the Russian counterparty in August 2025, we realized that Russia and China had maintained this scheme and created new shell companies to circumvent further sanctions,” sources added.

In response to inquiries from the Financial Times, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated that it does not have such information, adding that Beijing, while remaining neutral regarding the war in Ukraine, "consistently opposes unilateral sanctions that have no basis in international law and are not sanctioned by the UN Security Council" and will "resolutely defend the legitimate rights and interests of Chinese companies."

However, Sir Richard Moore, the former head of British intelligence MI6, stated shortly before his resignation in September that he has no doubt that Beijing's support has played a key role in prolonging the war.

“It is that support that China consistently provides to Russia—both diplomatic and in the form of dual-use goods, such as 'made in China' chemicals that end up in shells, and electronic components in missiles—that has prevented Putin from concluding that peace is the best option for him.”

Read also:

Zelensky spoke about the 20 points of the peace plan. What's new in it?

President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelensky presented a draft agreement for ending the war, which was...

Non-Combat and Unrecognized: Suicides in the Ukrainian Army That Are Silent

This is a translation of an article from the Ukrainian service of the BBC. The original is...

New Tactics of Russia Accelerated Offensive in 2025, - ISW Analysis

// picture alliance/AP According to ISW data, in 2025, Russian troops captured 4,831 square...

Aeon: How the Conquest of Foreign Territories Came to Be Considered Unacceptable

Author: Cary Goettlich In the modern world, there are fewer and fewer things that evoke consensus...

Problems of Diagnosing Hip Joint Dysplasia in Kyrgyzstan. Archival Interview with Kasymbek Tazabekov

In Kyrgyzstan, orthopedic diseases remain one of the key medical problems. According to the...

"War Will Change Beyond Recognition." Colonel of the General Staff of Russia — on the Lessons of Military Actions in Ukraine, Changes in the Army, and the Weapons of the Future

The conflict in Ukraine has not only become a catalyst for changes in the military sphere but has...

Tokayev: Kazakhstan has entered a new stage of modernization

Curl error: Operation timed out after 120001 milliseconds with 0 bytes received...

The J-1 Cultural Exchange Program in the USA has turned into a scheme for profiting from and exploiting foreign interns, - The New York Times

Another scheme involved employing close relatives of the CEO, which brought his family over 1...

How "Eurasia" is Changing the Daily Lives of Millions in Kyrgyzstan

Curl error: Operation timed out after 120001 milliseconds with 0 bytes received...

Zelensky, Macron, and Starmer Signed a Declaration on Guarantees for Kyiv and the Deployment of Troops in Ukraine After the Conflict Ends

During the "coalition of willing" summit in Paris, French President Emmanuel Macron,...

Life in the Regions: A Bullet in the Seat of a Honda — How One Detail Helped Investigator Kurmanbek Kanybek Uulu from Osh Uncover an Organized Crime Group

Kurmanbek Kanybek uulu — an investigator of the control and methodological department of the...

Zelensky listed 20 points of the peace plan that were discussed in the USA

Volodymyr Zelensky President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelensky announced 20 points of a peace plan...

Sadyr Japarov spoke at the IV People's Kurultai (text of the speech)

Today, December 25, the President of Kyrgyzstan, Sadyr Japarov, addressed the people, the deputies...

Merz Limited Himself to Vague Guarantees for Ukraine at the Meeting in Paris

At the summit of the "coalition of the willing" in Paris, Chancellor Friedrich Merz...

Like Another Planet. A Kyrgyz Person on Life in Papua New Guinea and Working at the UN

Kанагат Алышбаев, a native of the village of Sary-Kamysh in the Issyk-Kul region, holds a degree...

Nelly Nosalik: Advertising on Social Media - The Most Promising Direction

In Kyrgyzstan, there is a growing interest in women's entrepreneurship in the field of...

Rest in Goa: A Guide for Kyrgyzstanis on the Main Tourist Destination in India

Goa is one of the most vibrant and attractive tourist regions in India. Here, everyone will find...

Cinema as a Tool for Human Rights Protection: An Interview with Swiss Documentarian Stefan Ziegler

At the end of 2025, a ceremony for the "Ak Ilbirs" award took place at the National Opera...

The last days of the year will replenish the treasury. Horoscope from December 29 to January 4

The week leading up to the New Year inspires rest, travel, and celebrations. A key moment will be...

"Sometimes Harsh, but Necessary". How Entrepreneurs Assess the Year 2025

According to the analytical forecast of the Central Bank, it is expected that by the end of 2025,...

Chinese Projects in Tajikistan: Outbursts of Violence, Labor Conflicts, and Uncertainty

Chinese companies actively involved in Tajik mining projects, road construction, and industrial...

Tokaev gave a major interview to the Turkistan newspaper. It covers reforms, AI, nuclear power plants, Nazarbayev, and much more.

President Kassym-Jomart Tokaev shared his views on current challenges and achievements in his...

Our People Abroad: Selfies in front of the Eiffel Tower and Life in Doha: The Success Story of Aizhan Sadykova

Turmush continues to introduce Kyrgyzstani individuals who have found themselves beyond their...

Nostradamus' Prophecies for 2026: King Donald Trump, the Decline of the West, Widespread War, and AI

As 2026 approaches, interest in Nostradamus' "Prophecies" — the famous collection...

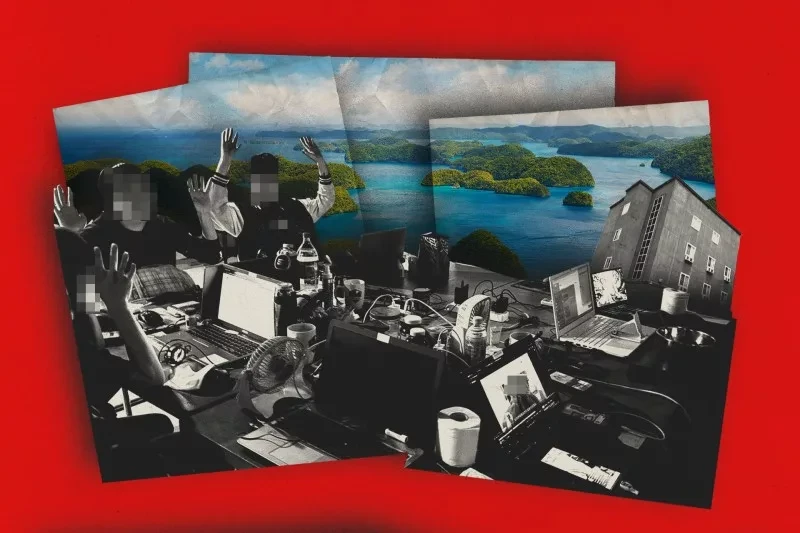

Foreign Workers, Local Sponsors: How Cyber Fraud Schemes with Hotels in Palau Are Organized

New data reveals the mechanisms of operation of two alleged fraudulent centers in Palau, a small...

Bishkek Enters the Cycle of Revaluation of the Royal Central Park Real Estate Market and the Advantage of Price Fixation in the First Three Years

The economy, which is on the path of rapid and stable growth, leads to an increase in real estate...

Events of 1986 in Almaty: What did Gorbachev say about Nazarbayev?

847169 24.01.2011 Former Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev with his daughter Irina Virganskaya at...

In Search of Hope: How Rescue Dogs Find People in Kyrgyzstan

In Kyrgyzstan, searches for missing people often start too late, when the chances of success...

Is Kazakhstan Awaiting a Water Collapse Following the Iranian Scenario?

The inability of the new Ministry of Water Resources to address the water shortage problem is...

British couple welcomed a homeless man on Christmas, and he stayed with them for 45 years

The situation that began as a temporary act of kindness led to 45 years of shared life filled with...

Piano for 25 million, 7 billion soms budget, demolition of cultural monuments. A large interview with the Minister of Culture Mirbek Mambetaliev.

АКИpress presents the results of 2025 in the field of culture in Kyrgyzstan, gathered from the...

Victory Over Oneself: How Sports Change the Lives of People with Disabilities

Photo 24.kg. Future champions are preparing for competitions In Kyrgyzstan, there are over 218...

How Were the Songs of Composer Zhanishbek Kochkorov Created?

Jalal-Abad Region, city of Kara-Kul. Here lives 71-year-old Janishbek Kochkorov — a honored artist...

Why Tourists Need Almaty, Not New York, Moscow, or Paris

Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, in an interview, emphasized the need to transform Almaty into a unique...

Canada fears it may become Trump's next target after Venezuela and Greenland

Canada expresses concerns that it may become the next target for Donald Trump's presidential...

Alibaba's Head: China's Chances of Surpassing the U.S. in AI Are Less Than 20%

At a recent conference in Beijing, artificial intelligence experts from China presented their...

Did Trump Exchange Taiwan and Ukraine for Venezuela?

Analyzing recent events, Jaykhun Ashirov reflects on why the theory of a conspiracy between the...

Exit from the EU blacklist and rules for drones: what is changing in the aviation of the Kyrgyz Republic

Photo GAGA Currently, the civil aviation of the Kyrgyz Republic is undergoing significant changes....

Stable, Pragmatic, and Gradually Developing Relations - Ambassador of Kazakhstan Rapil Zhoshybaev (Interview)

The Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Ambassador of Kazakhstan to Kyrgyzstan, Rapil Zhoshybaev,...

"Russia Gave Up Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and the Caucasus." The US Declassified Transcripts of Putin's Conversations with Bush

The published transcripts pertain to three meetings between Putin and Bush that took place in...

To Avoid Inflation and Preserve Value: What Should Investors in Bishkek Do?

In the context of global economic instability and the resurgence of inflation, the period from...

Voting - a right or a duty? The controversial bill of the deputy

Deputy Marlen Mamataliyev has proposed making participation of citizens of Kyrgyzstan in elections...

Sale of the former Prince Andrew's mansion to Kazakh oligarch Kuliayev for £15 million is linked to a bribery scheme, - BBC investigation

A BBC investigation has revealed that Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor received significant sums from an...

"Emotional Swings". Reforms, Scandals, and Year-End Results in School Education

While the long holidays continue, Kaktus.media summarizes the past year in the field of education,...

Kyrgyz is Logic. Victoria Krinwald on How to Quickly Learn the State Language

Victoria Krinwald, being of German nationality, has been living in Kyrgyzstan for 17 years, where...

The President of Chile is José Antonio Kast, a supporter of dictator Pinochet

José Antonio Kast, representing the far-right political force, has been elected as the President...

Project "Zheneke": She knows what will suit your car — how Nuraiym Bektiyanova surprises drivers

The regional news publication Turmush continues its column "Zheneke." In it, we share...

How Crypto Miners Stole $700 Million from People, Often Using Old Proven Methods

The theft of cryptocurrency evokes a particular, agonizing feeling. All transactions are recorded...