In Kyrgyzstan, there are over 218 thousand people with disabilities, yet only a small portion of them find their calling in sports. Paralympians representing the country, from powerlifters to athletes, face difficulties and prejudice daily, demonstrating that disability is not an obstacle to achieving international success. Their inspiring stories of spirit, perseverance, and self-belief serve as motivation not only for aspiring athletes but for society as a whole.

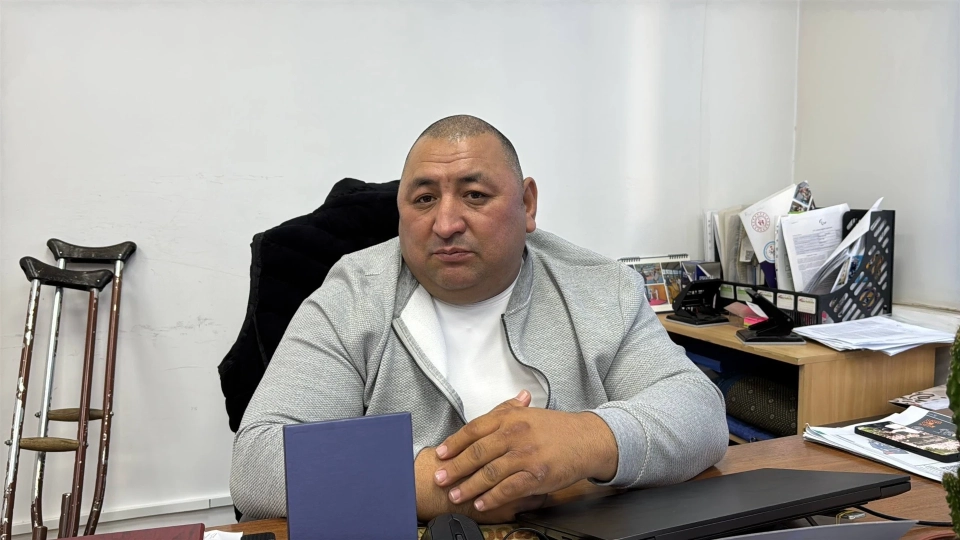

Toktorbek Aydyraliev, president of the "Kyrgyz National Paralympic Committee" and a master of sports in powerlifting and arm wrestling, shared with a journalist from 24.kg how young people with disabilities become successful athletes and how coaches literally have to pull them out of their homes to engage them in sports.

Origins of Paralympic Sports in Kyrgyzstan

“The Paralympic Committee was founded in 1994, when it was called the Federation of Disabled Sports. However, the training and performances of our athletes began back in the Soviet era. At that time, the main sport was only para powerlifting, and we trained alongside able-bodied athletes,” Aydyraliev recounted.

From 1994 to 2008, only this sport developed actively in the country, and our guys achieved impressive results at championships, becoming pioneers in parasports. For example, Roman Omurbekov is a participant in five Paralympic Games and one of the best athletes in the country.

In 2015, the growth of cycling parasports and athletics for people with disabilities began, including running for the blind and visually impaired, as well as shot put, javelin, and discus throw.

“We faced a shortage of coaches, and we had to train Arstanbek Bazar Kulov using YouTube videos. Thanks to his perseverance, he became a world champion and won the grand prix in shot put and discus throw. At first, we didn’t even have a metal shot put; we used stones, selecting the most suitable ones by weight,” Aydyraliev recalls.

In Bishkek, athletes have no special facilities and are forced to look for venues outside the city. Currently, they train at a sports school in Kant, which has a sand sector. Getting there is difficult, as throwing is prohibited at the capital's stadium to avoid damaging the lawn.

According to Toktorbek, winter training almost comes to a halt.

Challenges on the Path to International Competitions

In 2020, judo for parasports athletes appeared in Kyrgyzstan, and one blind athlete participated in the Paralympic Games in Tokyo. Despite losing in the first minute, it became a powerful motivation for her, and within a year, she trained hard and became a world champion.

“Paralympic sports are gradually developing. Women in wrestling are showing excellent results. Taekwondo athletes are also performing well, most of whom are young people with amputated arms,” Toktorbek added.

The country lacks sports doctors. Due to the absence of a clear classification of disabilities, athletes are often not allowed to participate in international competitions due to errors in their documents.

In the last five to six years, the government has started paying more attention to parasports athletes, providing awards, business trips, funding, and participation in competitions.

“Unfortunately, there is no centralized base. There are those willing to engage in sports, but they live far away. They are not Olympians who can just hop on a minibus and go. They need dormitories and training halls nearby,” Aydyraliev noted.

Training Issues for Sports Veterans

The head of the committee also touched on an important issue in parasports: many athletes who have trained for 20 years and have ended their careers cannot become coaches because there is no specialized training for them in the country's universities.

“I myself wanted to enroll in our Institute of Physical Culture, but all exams and standards are only for healthy people,” Toktorbek added.

Athletes with disabilities are true self-starters who create conditions for themselves independently. Despite the challenges, they strive for victory. The lack of equipment and inventory does not stop them—they create what they need on their own.

Sports is Life!

For Toktorbek, sports is his entire life. “I have been walking on crutches for 40 years, as I had polio in childhood. They say this disease occurs in one out of a thousand children. And I was that child,” he shares.

After the illness, Toktorbek's legs failed. His parents did everything possible for his treatment. By the age of five, one leg began to move.

At six, Toktorbek was sent to a boarding school, where he spent holidays receiving treatment at rehabilitation centers. His parents hardly saw their son, and in the 3rd or 4th grade, he refused to study and decided to return to his native village. After spending a year at home, he returned to a regular school, where he studied on crutches.

“After the ninth grade, I became the main helper and breadwinner in the family, as my father passed away. I worked wherever I could, and then I met guys who introduced me to powerlifting. This coincided with my teenage years when I wanted to socialize with girls. I started to wonder if I would have a family?” Aydyraliev recalls.

Toktorbek's Personal Record: How Sports Led to Love and Family

Toktorbek always felt shy about meeting and interacting with girls. However, sports changed his life, giving him confidence. He became a ten-time champion of the republic, and for ten years, no one could defeat him.

His father said he needed to find a girl with a disability, but Toktorbek wanted to marry a beautiful and healthy woman so they could have children.

At 25, he met a pharmacist, and they got married.

“At that time, we faced financial difficulties: my mother was diagnosed with diabetes, and medications were needed. I went to the pharmacy where my future wife worked and asked to lend me some medications. She agreed, and I immediately returned the money as soon as I earned it. That’s how we met, and we have been living together for 20 years, raising five children. Recently, I became a grandfather,” he recounts.

A Second Chance: How Former Beggars Become Champions

The president of the committee also shared the story of one athlete: “At the ‘Dordoy’ market, our guys met a young man with a disability who was begging. At first, he refused to communicate, having become accustomed to the cruelty of those around him: they took his money and insulted him. He only has three grades of education. After starting training, his life changed: now he is a champion who built his own house and left his past difficulties behind.

In his free time, Toktorbek drives a taxi. If he sees young people with disabilities, he tries to support them and invite them to sports, introducing them to coaches.

“Even my wife, when she is in the car and sees a potential athlete, asks to stop so she can invite them to us,” Toktorbek says.

All Doubts Behind

Para powerlifter Mirgul Bolotalieva, a participant in the Paris Paralympics, has a II group disability—paresis of both legs, resulting from polio she had in childhood.

“My fellow athletes had long invited me to powerlifting, but I thought this tough sport was not suitable for women. So, I refused for 10 years. But during the coronavirus pandemic, I decided to give it a try since sports mean health,” she shares.

At first, Mirgul trained cautiously, fearing that broad shoulders and powerful arms would not be appropriate for a woman. However, after participating in international competitions, she realized that it was not only cool but also interesting.

“Sports have become an integral part of my life; its value is hard to overestimate. It provides motivation and discipline, strengthens character,” the athlete emphasizes.

She noted that paralympic sports are beginning to gain popularity comparable to Olympic sports and are gradually developing worldwide, including in Kyrgyzstan. However, many people with disabilities still do not know about parasports and spend their lives in confinement.

Strength of Spirit and Weights

Esan Kaliev, diagnosed with cerebral palsy, started engaging in sports at a young age and has seen the meaning of his life only in it for over 20 years. He is a honored master of sports of international class and a coach.

“You shouldn’t stay at home and complain about your disability. Don’t be lazy, move forward. This is your life. Personally, I don’t complain about anything; I have everything for happiness: family and children. I’m glad that I do sports and involve others in it,” he added.

Sports is a Lifelong Pursuit

Alexander Prokopov, an arm wrestling coach and multiple Asian championship medalist, despite his diagnosis of “cerebral palsy,” teaches children and engages them in sports. He believes that for sports to become a life’s work, the desire of the individual is necessary, and for that, one just needs to come and watch how others train.

“I came to arm wrestling and powerlifting at 25, found a children’s sports school that accepted and trained me. Sports became the meaning of my life,” he concluded.

Paralympic sports in Kyrgyzstan continue to develop, although it still needs specialized halls and infrastructure. Despite this, athletes and coaches continue to demonstrate strength, discipline, and determination—some find confidence and family, others discover a new meaning in life, and some share their experiences with the younger generation.