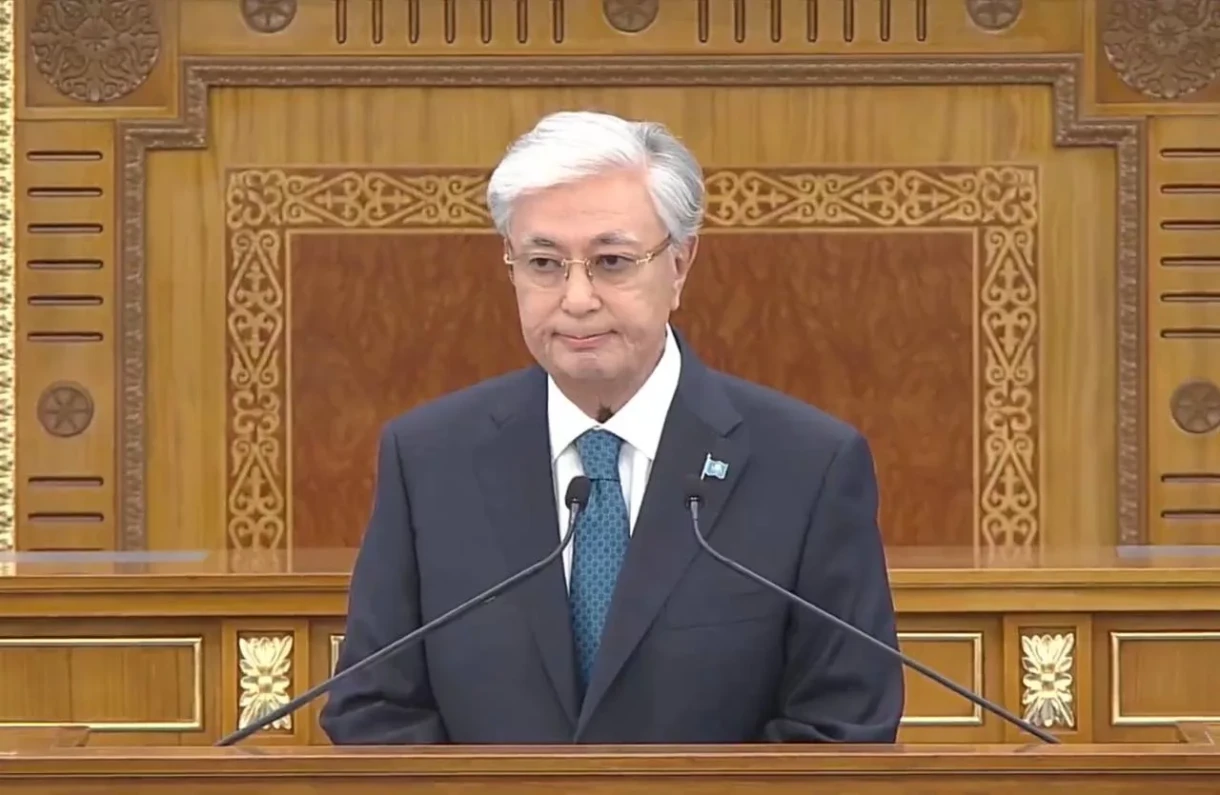

The question of whether boxing caused Muhammad Ali's Parkinson's disease sparks heated debates. In this material, we will examine various opinions on this topic.

There are claims that the Parkinson's disease from which Muhammad Ali suffered arose due to his boxing career. However, this opinion is disputed, and we will provide facts supporting an alternative viewpoint.

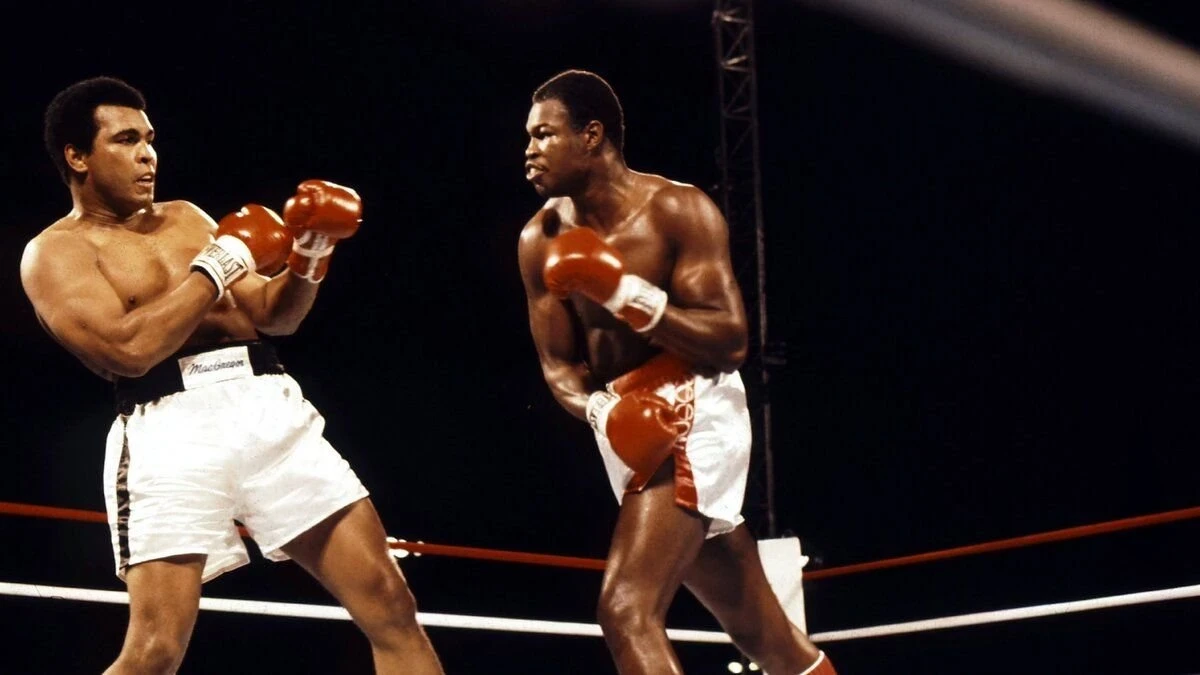

First of all, it is worth noting that Muhammad Ali was not just a great boxer, but a true icon of the sport, a poet in the ring who impressed audiences with his style — "floated like a butterfly, and stung like a bee."

Among those who have long been associated with the world of boxing, one can hear many stories about how this sport sometimes confronts harsh realities. However, one of the most common legends is the assertion that Ali's Parkinson's disease is directly related to his performances in the ring.

Undoubtedly, boxing is a sport with a high risk of injury, and concussions can have serious consequences. But upon careful analysis of medical data, expert opinions, and scientific research, it becomes clear that there is no connection between his illness and boxing.

Doctors and experts who treated Ali after his death in 2016 never pointed to boxing as the source of his illness. This is not just an opinion — it is the result of a comprehensive analysis of his medical history.

To understand why the connection between boxing and Parkinson's disease in Ali is a myth, it is important to consider the disease itself. Parkinson's disease is a neurodegenerative disorder that causes movement problems such as tremors and stiffness. It was first described by James Parkinson in 1817, and the exact causes of this disease remain uncertain to this day. In most cases, it is "idiopathic," meaning the cause is unknown.

Genetic factors play an important role; mutations in genes such as SNCA or LRRK2 can increase susceptibility to this disease. Research shows that there are links to pesticide exposure, but a direct connection to head injuries raises questions. The concept of "boxer's parkinsonism" arose from observations of boxers suffering from brain injuries, but this is a separate issue — rather, it is chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), which Ali did not have.

Ali was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease in 1984, three years after retiring from boxing. At 42, this is quite a young age for the onset of the disease, as it typically affects people over 60. However, it should be noted that early onset of Parkinson's disease is more often related to genetic factors than to external trauma. A 1999 study published in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry showed that cases of early onset, such as Ali's, often lack the characteristic signs of trauma, such as the accumulation of tau protein, which is observed in CTE.

Ali's symptoms began to manifest gradually in the late 1970s — a slight tremor in his left hand and slurred speech, which does not fit the concept of rapid deterioration that one might expect from cumulative injuries. Instead, the progression of symptoms corresponded to the typical course of idiopathic Parkinson's disease.

Now let’s turn our attention to Ali's medical team — the people who truly knew him and his health. Dr. Abraham Lieberman, who treated Ali for a long time at the center he founded in 1997, always emphasized that "there is no medical evidence" linking the disease to his boxing career.

He also mentioned Ali's family history — neurological problems in relatives that were never publicly discussed but noted in private consultations. Lieberman, a renowned neurologist who has treated over 40,000 patients with Parkinson's disease, stated that Ali's response to levodopa was typical for the idiopathic form of the disease, rather than the traumatic form, which often does not respond to such treatment. "Muhammad did not regret boxing," Lieberman said, not claiming but based on years of experience, that boxing was not the cause of his illness.

Dr. Holly Shill, who took over as director of the center, also confirmed that "there is no medical evidence" indicating a link between boxing and Ali's Parkinson's disease.

Thus, the myth that boxing caused Muhammad Ali's Parkinson's disease can be considered debunked.

An important aspect of the research is that Ali's symptoms developed differently than those of boxers who exhibit traumatic injuries. Ali had classic signs of the idiopathic form of the disease, such as stooping and a slowed gait, but without the cognitive impairments characteristic of CTE. Shill's team analyzed fight records and public appearances to identify the nature of the tremor.

Their research showed that Ali's tremor was asymmetrical and manifested at rest, which corresponds to the genetic form of Parkinson's disease. Studies conducted after his death also confirm that the disease had an early onset and was associated with genetic factors rather than trauma. The Emory University team, which monitored Ali's condition, conducted regular examinations for over 20 years.

Dr. Michael Okun, a leading expert in Parkinson's disease, along with colleagues who treated Ali, published an article in 2022 that presented evidence of idiopathic Parkinson's disease with early onset for the first time. They noted that while head trauma is usually a risk factor, in Ali's case, "causal relationships cannot be established."

The article details the unique aspects of Ali's condition: brain scans in the 1990s did not reveal damage characteristic of repeated concussions. Dopamine levels responded well to treatment, unlike cases of post-traumatic parkinsonism. An important point was that serial tests revealed progressive impairments consistent with classic Parkinson's disease, rather than "shock stupor" syndrome. Okun and his team emphasize that speculation without accurate data can be dangerous and debunked many rumors that appeared in the media. They never linked the disease to boxing; moreover, they actively refuted this connection.

As for surgeons, Ali did not undergo brain surgeries related to Parkinson's disease. However, his consultations with neurosurgeons in the early 1980s show interesting points. Records of these visits, mentioned in a 2022 JAMA article, indicated "possible" injuries, but the diagnosis was made as parkinsonian syndrome without establishing a causal relationship.

Dr. Stanley Fahn, who first diagnosed the disease in Ali, also mentioned that the symptoms were "too early for classic Parkinson's disease," but even he did not provide evidence for his hypothesis, limiting himself to assumptions. After Ali's death, Fahn noted that one cannot definitively state that boxing caused his illness.

An important aspect is that Fahn's team analyzed Ali's speech before his diagnosis and found a slowing down; however, in a joint study with ESPN in 2017, this was explained as early idiopathic onset of the disease rather than a result of punches.

After Ali's death on June 3, 2016, the medical community continued to assert that there is no evidence linking his illness to boxing. For example, the McKnight Brain Institute at the University of Florida published a conclusion in 2022 stating that the disease manifested in the middle of his career and was idiopathic in nature, responsive to levodopa treatment, rather than caused by trauma.

Research also points to possible pesticide exposure to Ali during training in rural areas. A meta-analysis from 2000 showed a link between pesticides and an increased risk of Parkinson's disease — a higher rate than for head injuries. Ali's family, including widow Lonnie, points to this, and Lonnie mentioned in a 2017 interview that Ali trained near farms where potent chemicals were used. This opinion is supported by many experts, including the Michael J. Fox Foundation, which considers various factors, including genetics and environment, as important for the development of the disease.

It is important to emphasize that the diagnosis of Parkinson's disease is made based on clinical symptoms and response to treatment, not laboratory tests. Ali declined an autopsy, which did not allow for definitive causes to be established. A 2018 study conducted on 50 former boxers showed that only 20% of them with Parkinson's disease had a connection to injuries, and Ali did not meet their criteria. Estimates suggest that the number of punches Ali received did not exceed 1,000 over 61 fights, which is significantly less than many other boxers who had confirmed cases of CTE but not Parkinson's disease.

Ali's style, which involved evading punches rather than absorbing them, also contributed to minimizing injuries. A 2017 biomechanical analysis showed that his rate of head injuries was 40% lower than the average for heavyweights.

Critics may refer to general studies linking traumatic brain injury to an increased risk of Parkinson's disease, but these are correlations, not causal relationships, especially in Ali's case. Dr. Rodolfo Savica from the Mayo Clinic stated in 2016 that genetic predisposition plays a key role, and trauma may only "enhance" it.

Since 2016, Savica's team has conducted studies on athletes and found no direct link in boxers without genetic markers. Ali's genome has not been publicly studied, but his family history points to the LRRK2 mutation, which is common in early-onset disease.

Ali's life journey is also important. He founded his center to fight Parkinson's disease, never blaming boxing for it. At Senate hearings in 2002, he spoke with Michael J. Fox about the need for research rather than regrets. His daughter Laila, also a boxer, noted in 2017: "Dad's Parkinson's disease was his burden, but not from the ring — it was fate." Unique data on Ali's training in the 1970s shows the possibility of contaminated water exposure, which could also be a risk factor.

It is important to pay attention to the perception of the issue in the media. Journalists often emphasize the stereotype of "punch-induced concussion," but many specialists refute this. For example, Dr. John Trojanowski from the University of Pennsylvania, upon meeting Ali, expressed an opinion about the likelihood of a connection but later clarified that it had not been proven. A 2016 Time magazine article also mentioned family beliefs reflecting the opinion of the medical community.

From the perspective of genetic factors, it is interesting that Ali's Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry is associated with increased expression levels of the LRRK2 gene. Combined with training in rural areas, this creates unique circumstances that have nothing to do with boxing.

In scientific circles, the conclusion is clear: there is no evidence that boxing caused Ali's Parkinson's disease. His doctors, such as Lieberman, Shill, and Okun, never linked the disease to his boxing career. Modern research confirms this, emphasizing uncertainty. Boxing, of course, carries risks, but for the "Greatest," it was merely a distraction.

In conclusion, Ali's legacy is defined not by his Parkinson's disease but by how he fought against it. He raised millions, inspired research, and showed resilience. As a passionate boxing fan, I believe we should honor his memory by discarding myths and embracing facts. Boxing gave us Ali, and Parkinson's disease was just another opponent he defeated.