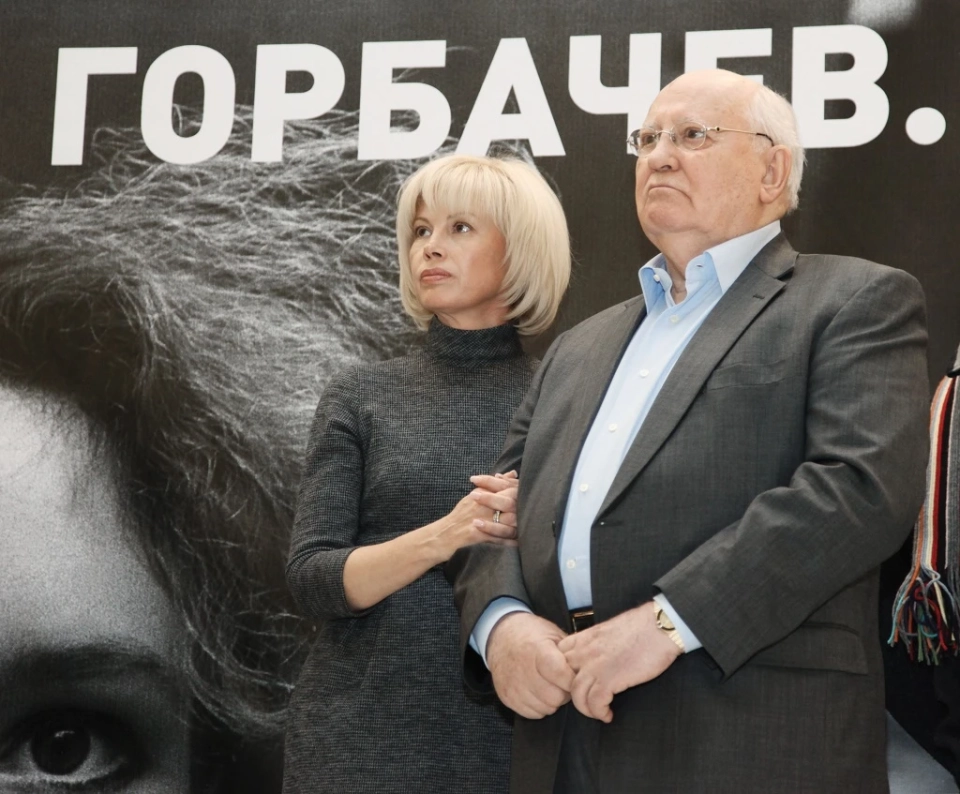

Nikita Khrushchev once remarked: "By deciding to embrace the 'thaw' and consciously moving towards it, the leadership of the country, including myself, was simultaneously apprehensive: what if it leads to a flood that would overwhelm us and make it difficult for us?" The events of those years, when Khrushchev's thaw swept across the Soviet Union from the death of Stalin to the arrival of Brezhnev (1954-64), remain an important chapter in history. What will the 'thaw' look like in Kyrgyzstan?

The term "Khrushchev's thaw" refers to the course towards the democratization of public and political life in the USSR. A crucial aspect of the reforms was the dismantling of the cult of personality and the destruction of the ideological system that had existed since the 1930s. The main signs of the thaw include the flourishing of culture and public life, the easing of censorship, and the rehabilitation of the repressed. People who were executed under Stalin received posthumous rehabilitation, while others were released from prisons and granted freedom.

After Stalin's death, society was filled with conflicting feelings. On one hand, Stalin was a symbol of victory over fascism and the restoration of the country; on the other hand, millions of Soviet citizens suffered from repression and yearned for freedom. The emergence of Nikita Khrushchev as the leader of the country sparked hope and optimism: people began to tell political jokes without fearing for their safety.

The official start of the thaw was marked by the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in February 1956, when Khrushchev delivered his famous de-Stalinization speech.

Interestingly, the Kyrgyz 'thaw' is expected in February 2026, exactly 70 years later.

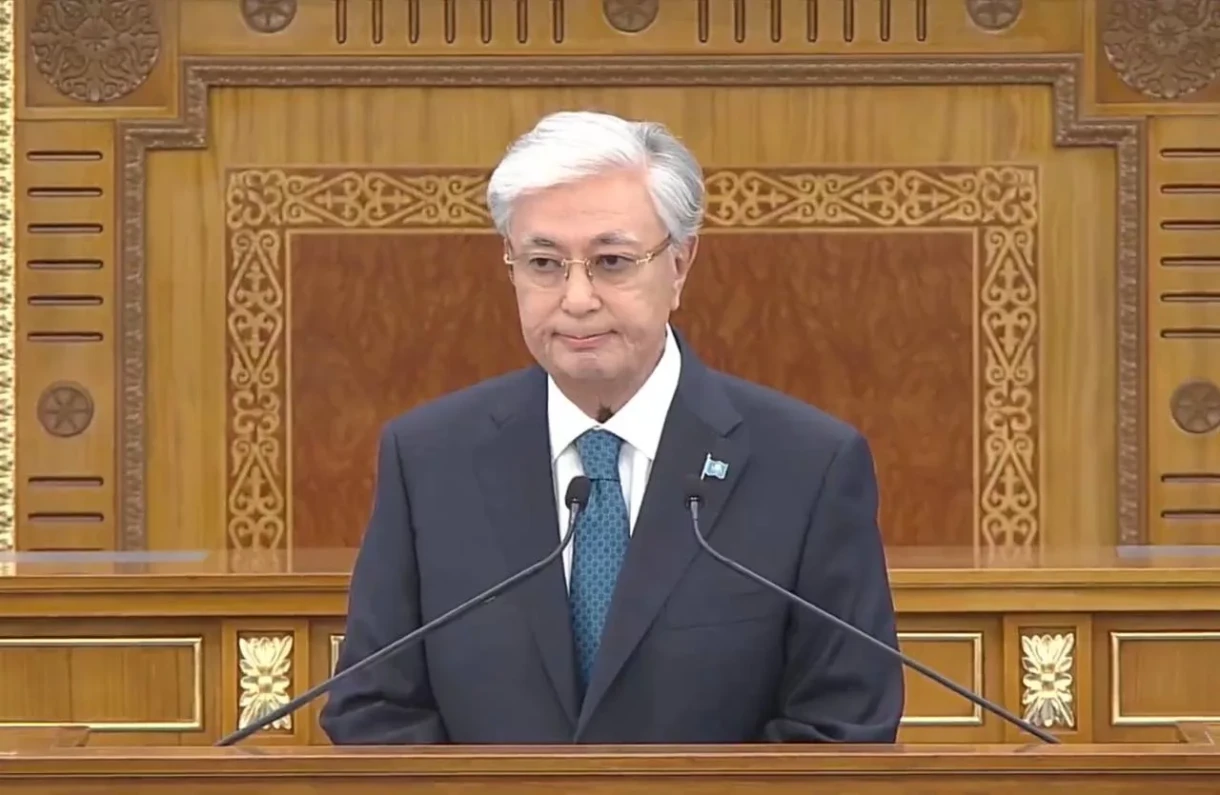

In his speech, Khrushchev pointed out the cruelty of the previous regime, when innocent people were seized on the streets, tortured, and executed without trial. Sadyr Japarov, commenting on the dismissal of Kamchybek Tashiev from the position of head of the State National Security Committee, also noted some excesses at the local level, emphasizing that the Committee had fulfilled its mission and, in some aspects, even exceeded it. Khrushchev acknowledged that in certain historical moments, harsh measures were necessary, and Japarov agrees that five years ago, the national security agencies faced serious challenges that required tough actions. However, the situation has now changed, and state institutions must adapt to new conditions.

In his famous 1956 report, Khrushchev also criticized Lavrentiy Beria, the former head of the NKVD, whom the population feared, labeling him as a torturer and enemy of the people. Modern historians, decades later, are reassessing his role in Soviet statehood, noting the complexity of his personality.

The people of Kyrgyzstan appreciated Kamchybek Tashiev's work immediately, without waiting for new interpretations of historical events. Tashiev is held in high regard, as his principled stance helped resolve many border issues that could have exacerbated the situation in the country.

Politician Felix Kulov reminded of the president's speech at the Kurultai, where Japarov mentioned instances of abuse of power by law enforcement officials in the fight against banditry and corruption.

Deputy Prime Minister Edil Baisalov commented that some representatives of the law enforcement agencies began to overstep their authority, creating an atmosphere of fear in society.

The period of cruelty has come to an end, and it is time to strengthen legality and the presidential republic.

According to Edil Baisalov, "power must be clear, constitutionally defined, and concentrated in one center of responsibility." President Japarov is obliged to ensure the unity of the state, maintain stability, and uphold the supremacy of the Constitution, avoiding the usurpation of power in any form. The era when certain bodies possessed powers that were not characteristic of them must remain in the past. We must move towards a mature rule of law state, where each authority acts strictly within its functions.

Thus, the President of the Kyrgyz Republic, Sadyr Japarov, takes on all levers of power, becoming a full-fledged head of state, as provided by the new Constitution, thereby eliminating chaos and uncertainty in society. He is softening the harsh power regime and ushering the people into a 'thaw.' Although Khrushchev disliked the very word, associating it with slush, those are his personal associations.

What is most important in the thaw? The main thing is to prevent the "flood" that Khrushchev worried about seventy years ago.

In the 1950s, many of those whom the Stalinist regime sent to camps finally gained their long-awaited freedom. However, alongside the political prisoners, criminal elements were also released, leading to a sharp rise in crime.

Society became so liberal that an entire generation of free-thinking individuals, unashamed of either external or internal censorship, ultimately overthrew both the power and the system, offering nothing more constructive.

Will something similar happen in Kyrgyzstan? Will the country be overwhelmed by a wave of released "prisoners of conscience," among whom there will be many criminals? Will the courts cope with the influx of reviewed criminal cases and be able to separate those who should not have been imprisoned from those who must face serious punishment? Will the "free and independent" spirits rise up, ready to undermine state foundations under foreign funding?

One way or another, there will be no return to the past. Kyrgyzstan is entering a new phase of its existence and development. "Sometimes you think: it's all over, the end. But in reality, this is the beginning. Just the beginning of another chapter" (Ilya Ehrenburg, novella "Thaw," 1954).