In an interview with 24.kg, Mahabat shared her impressions of life in Germany and the significance of the Kyrgyz language.

Photo from the interviewee's archive. Mahabat Sadyrbek

— I was born and raised in Kyrgyzstan, where I graduated from school No. 71 in Bishkek. In my third year at university, I managed to receive a DAAD scholarship, which brought me to Germany in 1999. I currently live in Halle, near Berlin, and sometimes travel to Turkey for treatment.

— How was your adaptation to life in Germany? Was it easy to get used to the new cultural conditions?

— I liked the country right away, and after a five-month scholarship, I continued my studies. The adaptation was gradual: I mastered the language faster than I got used to the peculiarities of the local system and way of life. German culture demands high precision and discipline. I completed my bachelor's degree, master's degree, attended a school of diplomacy, and defended my dissertation. Over time, I became part of the professional community, although migration left me with a sense of duality — being both "inside" and "in between".

— What surprises you about Germany?

— I am struck by the stability of institutions, respect for knowledge, and attention to detail. However, bureaucracy and the formalization of human relationships sometimes pose challenges. One of my most significant impressions has been that efforts and knowledge are truly valued and supported. Scholarships and funding have played an important role in my perception of the country and my further professional path.

— How is the job market in Germany? Is there high competition?

— Competition in the labor market is quite high, especially in fields with many specialists. Immigrants often need more time to validate their qualifications, but with a clear professional profile and recognized documents, the system works fairly transparently. I have been working in academia for over 25 years, which is inherently international and interdisciplinary: here, the focus is on projects and the quality of expertise, while a person's background takes a back seat.

— Since 2021, you have been a sworn translator of Kyrgyz, German, and Russian languages. Do you need special skills for this work compared to regular translation?

— Yes, in Germany, the profession of a court translator is strictly regulated and requires official appointment and ongoing qualification verification. As the Kyrgyz-speaking community grows, the need for professional court translation has become evident, and this demand has defined my professional path.

Court translation involves not only knowledge of the language but also a high degree of responsibility, understanding of the legal system, ethics, and procedures, as well as requiring concentration and discipline.

Mahabat Sadyrbek

As the only translator of the Kyrgyz language in Germany, I often work without the possibility of cross-referencing established practices, and all responsibility for accuracy lies with me. However, this is also a source of professional pride: the Kyrgyz language is gaining official recognition in the legal system, and my compatriots can understand foreign laws in their native language. Thus, the language expands its boundaries by mastering a new legal context.

— You have participated in translations of artistic, popular science, and documentary films, as well as literary works. Which project has been the most memorable for you?

— I am always attracted to projects where language intertwines with cultural context — artistic and documentary films, as well as literary texts. It was particularly interesting to work on films by Aktan Arym Kubat and the theater production "Nest," which was shown in Berlin last year. In such moments, I feel like a mediator and a "bridge" between two worlds, rather than just a translator conveying the meaning of words.

— Is there a work that you dream of translating in the future?

— I would like to work with historical films such as "Kurmandzhan Datka," "Kara Kyrgyzdar," "Syngan Kylch," as well as with documentaries about Urkun. I believe it is important to translate such works for a German audience to help them comprehend and process historical events.

Particularly, translating the trilogy "Manas" in the version of Sayakbay Karalaev would be a serious challenge for me — I grew up with this epic.

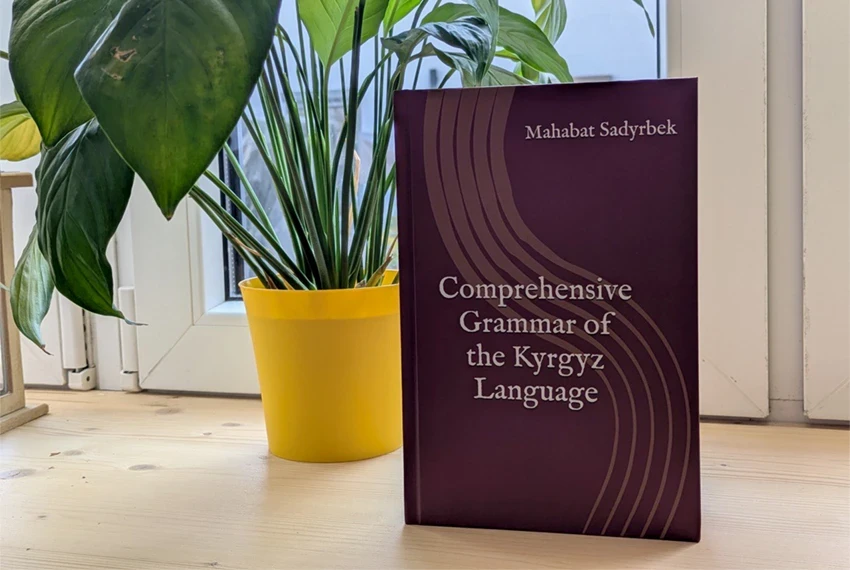

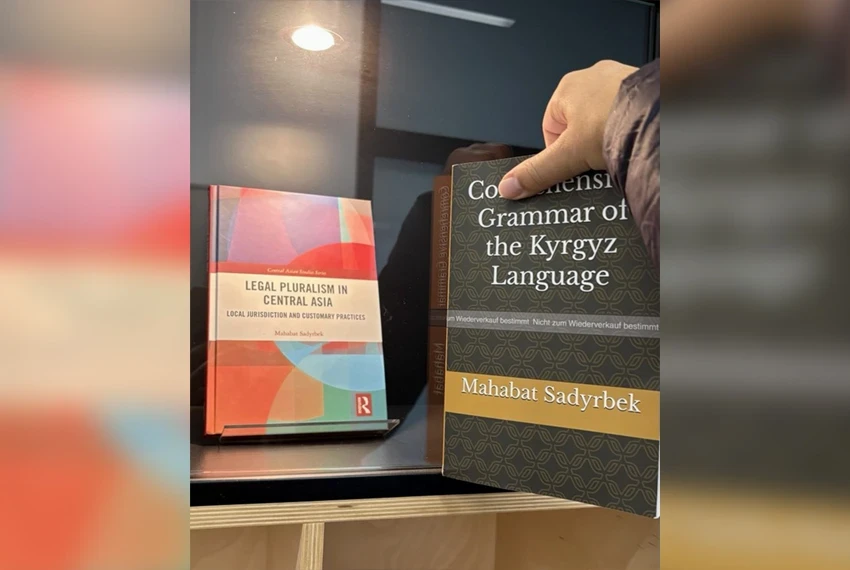

— How long did you work on the book "Complete Grammar of the Kyrgyz Language," and what prompted its creation?

— The work on the book took many years. The impetus was the realization that the Kyrgyz language is virtually absent in the form of modern, systematic grammar for an international audience, and I sought to fill this gap. A project that began as a hobby turned into a comprehensive long-term effort that I pursued alongside my main professional activities.

As a result, two substantial works of an encyclopedic nature emerged — in German and English. The latter most fully summarizes my knowledge and skills in linguistics and reflects the structure formed during the study of various languages.

— What aspects of the language were difficult to explain to an English-speaking audience?

— The structure of the Kyrgyz language differs significantly from Indo-European languages: agglutination and the law of vowel harmony present serious challenges for English speakers. Some aspects remain ambiguous, such as the future tense category, which is often interpreted as modal. Participles are also complex. Overall, working on the verb system of the Kyrgyz language required significant time investment and thorough research, where it was important to find a balance between scientific accuracy and accessibility of presentation.

— What feedback have you received about the book so far?

— I receive warm responses from Kyrgyz historians, linguists, and journalists who consider this work an important contribution to the preservation of the language and historical memory. The feedback from the Kyrgyz diaspora abroad is particularly touching: many are glad that there is now a solid foundation for teaching the native language to children who have grown up outside Kyrgyzstan.

Foreigners are actively studying the Kyrgyz language in Bishkek and beyond. In a specialized Facebook group with over 10,000 members, I have received many sincere and supportive comments.

However, many write about difficulties in acquiring the book, as Amazon does not yet deliver to Kyrgyzstan, and it is important for me to find a solution to this problem. For colleagues-linguists and researchers of Central Asia, the book has become proof that the Kyrgyz language can and should be considered a full-fledged object of modern scientific analysis.

— Are there currently enough quality educational materials to promote the Kyrgyz language? What is lacking?

— Unfortunately, there are not enough quality educational materials to promote the Kyrgyz language today. If you search for "Kyrgyz language," you can find only a few publications suitable for teaching, and only a few of them are truly useful.

The last relatively systematic educational resource of international level was created back in 2009 with the support of the Soros Foundation.

Mahabat Sadyrbek

There is a lack of modern, systematic, and multilingual materials designed for both adults and children.

— What is your main advice for those living abroad but wanting to preserve their native language?

— My main advice is to "live" in your native language more often: read, write, speak, and pass it on to your children without hesitation. I see many inspiring examples where parents create a language environment — organizing clubs, readings, theater productions, or film screenings. Ultimately, the language is preserved where it is loved and where speakers take responsibility for it.

— What do you miss most while away from your homeland? How often do you return to Kyrgyzstan?

— I miss the spontaneity of communication, the living intonations, and familiar landscapes. I come to Kyrgyzstan whenever I have the opportunity, but unfortunately not as often as I would like.

— How do you find a balance between work and personal life?

— It is a constant process. I am learning to set boundaries, leave time for myself, and take care of my health. I have an autoimmune disease that I have lived with for many years, so it is especially important for me to maintain a rhythm and treat my strengths with care. This has been one of the reasons I chose the path of independent work in science and translation — it allows me to organize my life according to my physical capabilities. I receive regular treatment, including in Turkey, and I try to distribute my energy wisely to be able to work and implement long-term projects.

— How do you see your near future?

— In five years, I plan to continue my academic and translation work, deepening projects related to language and cultural mediation. It is important for me to create sustainable resources for learning the Kyrgyz language and work at the intersection of science and public practice. I would like to develop international cooperation and participate in projects where language serves as a tool for conscious dialogue between cultures. At the same time, it is important for me to maintain a balance between professional fulfillment, personal responsibility, and quality of life.

I want the language to be perceived not as a symbol of the past but as a living resource for the future — in the dialogue of cultures and societies.

Against the backdrop of public debates about the relationship between the Kyrgyz and Russian languages, I want to emphasize: the Kyrgyz language should not develop in opposition to other languages.

Mahabat Sadyrbek

It develops on its own path — as a conscious choice, as part of identity, and at the same time exists in a multilingual space, coexisting and respecting other languages.