Since the beginning of January, a project for a new Constitution has been actively discussed in Kazakhstan. The discussions have involved a wide range of people, which is quite understandable given the importance of the country's fundamental law. As Daniyar Moldabekov notes, the authorities' reaction to these discussions has also turned out to be predictable.

On one hand, the Center for Combating Disinformation, operating under the SCK, published a refutation of several claims. While I do not assert that this statement is the only correct one, it is worth noting that the authorities did not resort to contemptuous threats against citizens who showed interest in changes to the Constitution. At the same time, they reproached society for its tendency towards clickbait, which, in my opinion, is not always fair.

The authorities' reaction in this regard was relatively correct: they made an official statement in response to the discussions. However, the Ministry of Internal Affairs also got involved, stating that "expressing opinions and positions is not a violation of the law," but at the same time did not refrain from threats of criminal liability for spreading "knowingly false information."

It should be reminded that "spreading knowingly false information" is a clause in the Criminal Code. Numerous lawyers and human rights defenders have been calling for the liberalization of this article for years due to its vague wording, which allows for overly broad interpretations of the laws. The Union of Journalists, to which I do not belong, has also stated the need to exclude this article from the Criminal Code.

My colleagues correctly pointed out that such issues should be resolved within the framework of civil law, rather than criminal law. Nevertheless, the Ministry of Internal Affairs expressed its readiness to "respond harshly to any attempts at destabilization." In my opinion, such threats are excessive, especially considering that it was the authorities who unexpectedly decided to update the Constitution, not the citizens.

Thus, the primary responsibility for any potential "destabilizations" should lie with the Akorda and the executive branch, including the Ministry of Internal Affairs. If it weren't for this dubious haste with the new Constitution, there would be no panic.

Today's times are complex: the population is burdened with loans and does not understand what will happen next. The rest of the world is engulfed in chaos and violence. Scaring a weary population with threats can also lead to destabilization, which no one desires. Everyone wants to live in a free and civilized country, and the authorities must also demonstrate democratic principles.

The Akorda creates an aura of reform around the Constitution project, but the propaganda work is done clumsily and ineptly, remaining within the framework of the usual approach. The process of "reforms" is accompanied by outdated propaganda. Politicized posts on Facebook are filled with template statements that could have been written by artificial intelligence.

Many things can be written into the Constitution, but it is much more difficult to fulfill those promises. When promising reforms, old methods cannot be used — otherwise, absurdity may lead to real "destabilization."

Political scientist Dosym Satpaev asserts:

The Pareto principle, according to which 80% of results are achieved through 20% of efforts, can also be applied to the project of the updated Constitution of Kazakhstan.

This Constitution is called "updated," not "new," since even the introduction of a unicameral parliament and a people's council does not change the main function of the fundamental law in the existing system — to create mechanisms that limit society's participation in political life.

It is important to note that, while promoting the new constitutional reform, the authorities, on the contrary, expanded the tools for limiting citizens' electoral rights.

Firstly, the introduction of only a proportional model for forming a unicameral parliament through party lists limits both passive (the right to be elected) and active (the right to vote) rights of citizens, as non-party candidates can no longer run independently, and voters who do not support any party lose the opportunity to express their opinion.

Secondly, the updated Constitution retains the discriminatory norm regarding presidential elections, according to which only a citizen with at least five years of experience in government service or elected positions can be elected president, which excludes a large portion of citizens from participating in elections.

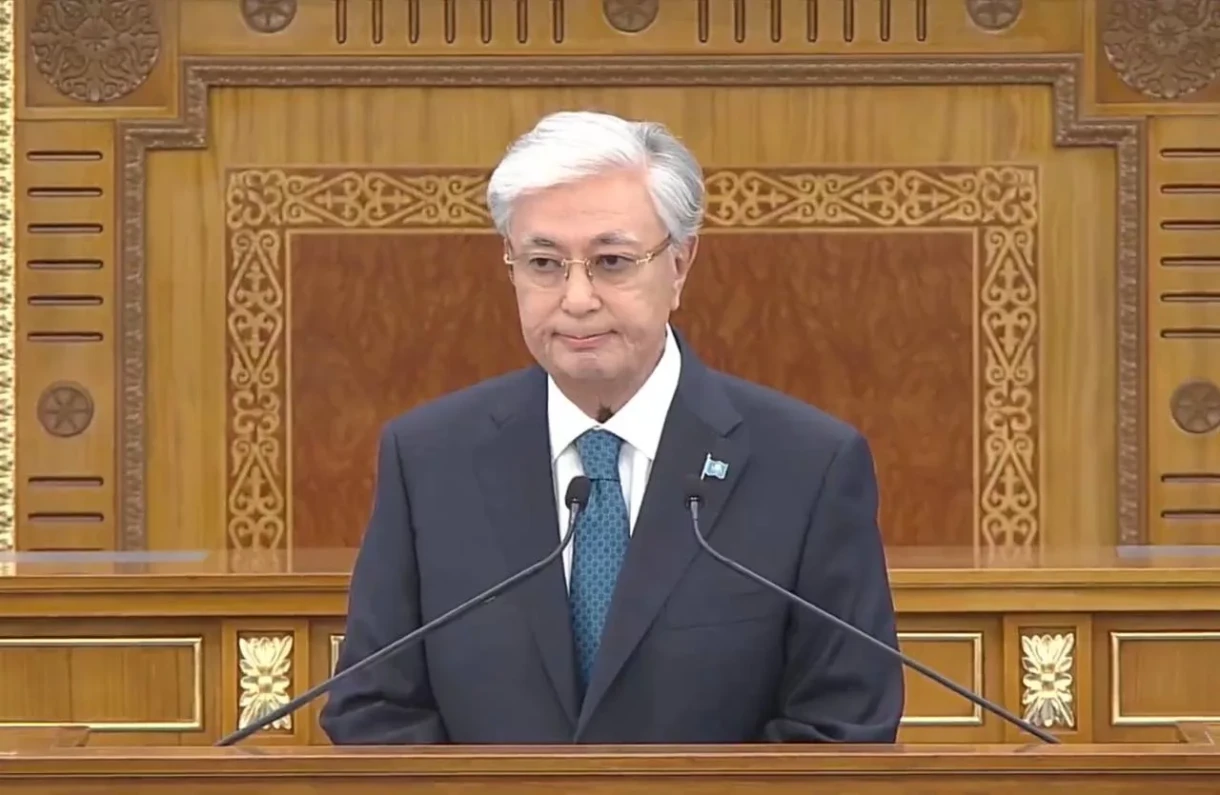

Interestingly, while K. Tokayev currently admires D. Trump and his initiatives, under the "updated" Constitution, Trump, just like under the "old" one, would have had no chance of becoming the president of Kazakhstan.

Thus, according to the Pareto principle, only about 20% of the articles in the Constitution hold the most significance for the authorities, and most of them are aimed at preserving political monopoly.

This 20% also includes new vague formulations that open up possibilities for various interpretations and abuses, threatening freedom of speech and citizens' rights to assemble.

When representatives of the authorities begin to talk about "morality," it should raise alarm, as they themselves are not a model of spirituality to determine what is moral and what is not.

In a political monopoly, any criticism of the authorities can easily be declared immoral. In the absence of clear legal definitions, the interpretation of morality becomes the prerogative of state bodies.

Authoritarian systems often encounter contradictions between laws and the Constitution. Formally, the supremacy of the Fundamental Law is maintained, but in practice, the will of the head of state or decisions of executive bodies can violate the constitutional rights of citizens, hiding behind the interests of the state or national security.

However, under the concept of "national security," the "security of ruling groups" is often implied, which leads to a desire to expand opportunities for arbitrary interpretation of the Constitution, laws, and regulations, justifying the adoption of restrictive laws that contradict declared rights.

One of the reasons for this is the weak constitutional control by the bodies responsible for law enforcement. The absence of a system of checks and balances leads to the dependence of the judiciary and legislative power on the executive.

Creating an effective system of checks and balances is fundamental for any serious constitutional reform. Without it, no matter how many rights and freedoms are enshrined in the Constitution, there will be very few real defenders of those rights.