Farmers living in the Syrdarya region claim that authorities are seizing their land under the pretext of debts and releasing it for Chinese investors. Similar actions are observed in other regions, as noted by Azattyk Asia.

Disputes over land rights affecting the eastern regions of Uzbekistan have reached the Syrdarya region. Farmers report that local authorities are using judicial and administrative methods to transfer agricultural land to foreign investors, primarily from China.

Gairat Usmonov, a farmer from the Khavast district, lost his leased plots in 2021 when they were handed over to a Saudi investor. After three years of legal battles, he managed to temporarily regain the land in 2025 when the investor abandoned the plot.

Now, according to Usmonov, local authorities are once again trying to seize his land, this time allegedly for Chinese investors.

Usmonov claims that he is being accused of illegally growing rice, which under the terms of his contract could lead to the termination of the lease. According to Uzbek law, agricultural land can be leased for up to 49 years, and the state has the right to terminate the contract for certain violations, such as non-payment of rent or improper use of the land.

Despite not having grown rice, Usmonov asserts that officials have taken his case to court, using this accusation as justification for terminating the contract.

“Facts are not considered,” Usmonov says in an interview with the Uzbek service of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (Ozodlik). “The court is always on the side of the authorities.”

Usmonov's story is one of many arising against the backdrop of the adoption of a law last May to create regional "directorates."

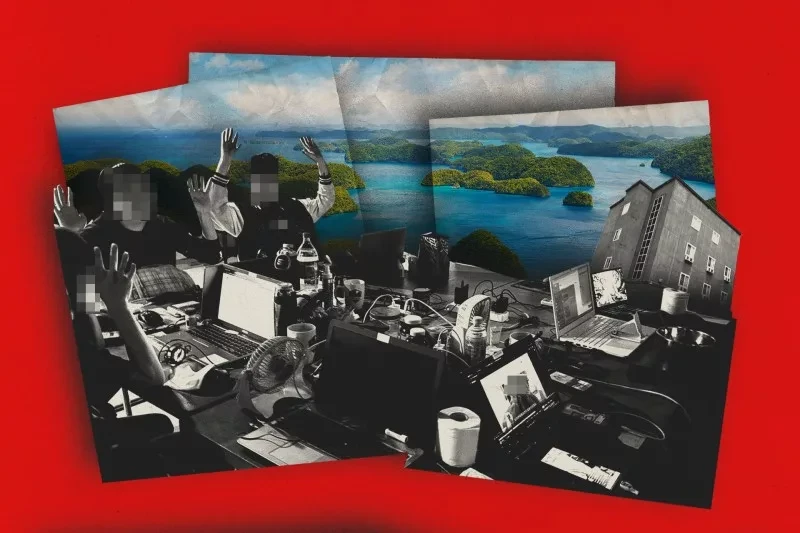

Authorities claim that this initiative is aimed at collecting debts and optimizing land use; however, farmers who spoke with Ozodlik (many of whom wished to remain anonymous due to fear of reprisals) believe it serves as a tool to displace locals from fertile lands and transfer them to foreign investors.

Usmonov and other farmers from the Khavast district reported that a large-scale campaign to seize land began in January. More than ten farmers told Ozodlik that nearly half of the farms in the district could be transferred to the state land reserve under the new system.

“The land is going from farmers to the state reserve, then to the directorate, and then to the investor,” one farmer said. “But no one is asking about the fate of those who find themselves at the center of this situation.”

A PATH FOR CHINESE INVESTORS

Although farmers claim that the main beneficiaries of land transfers in the Syrdarya region are Chinese companies, authorities do not confirm this information. However, last year Ozodlik reported that land plots in several districts of the Andijan region were being transferred to Chinese investors.

After the publication, land transfers temporarily ceased, but farmers assert that pressure resumed with the establishment of the new directorate system. Ozodlik examined this system in January and found that directorates began leasing land seized from farmers to Chinese investors.

With the enactment of the law creating the directorate system, offices responsible for monitoring land use and transferring agricultural land for sublease to local and foreign investors were opened in seven regions of Uzbekistan: Andijan, Jizzakh, Namangan, Syrdarya, Tashkent, Fergana, and Kashkadarya.

The main foreign investors are companies from China, which have increased their presence in Uzbekistan's agriculture through financial investments, infrastructure projects, and technology. In 2024, Uzbekistan approved a $220 million loan from the Export-Import Bank of China for the implementation of irrigation projects to be carried out by Chinese state companies such as CITIC Construction and China CAMC Engineering.

In 2025, delegations from Chinese agro-companies and local authorities visited the eastern and central regions of Uzbekistan, and in December, a group of officials from the Syrdarya region visited China to deepen cooperation in agriculture.

Farmers from the Khavast district told Ozodlik that Chinese investors were initially offered unused or degraded plots, such as overgrown lands or abandoned plots of former collective farms, but they refused.

“Investors demand fertile lands that are already being cultivated,” one farmer says. “These lands have been improved by our farmers over the years, despite difficult conditions.”

Local farmers estimated that this year, up to 17,000 hectares of land in the Khavast district are planned to be transferred, primarily into the directorate system and then subleased to foreign investors.

According to their estimates, this will affect about 300 farms, in addition to more than 10,000 hectares that have already been seized since the end of 2024 based on court decisions or under pressure from authorities.

“I WILL TAKE EVERYTHING”

Farmers who interacted with the new directorates claim that the system operates with the consent of high-ranking regional officials, including the regional hokim Erkinjon Turdimov.

The press secretary of Turdimov, Manuchehr Mirzaev, did not respond to Ozodlik's requests for comments regarding the seizure of agricultural lands and farmers' accusations of pressure on them.

“He started threatening people,” a farmer recounts. “One person said he owed a billion soms ($81,330) because he invested in drip irrigation and is gradually repaying the debt. The hokim replied: ‘You will be left on the street. I will take everything from you, even your house.’”

Farmers report that they are given a choice: either voluntarily give up the land—in which case authorities promise to settle debts after redistributing the plots—or refuse and face land seizure and debt collection.

According to one farmer, during a meeting with officials, police were stationed at the doors to prevent people from leaving. Farmers were called in one by one and forced to sign documents.

Those who refused to sign immediately faced consequences.

“The next day, property confiscations began,” a farmer recounts. “Officials came to homes and took everything—TVs, livestock, anything they could.”

PRESSURE FROM ABOVE

District authorities claim that the confiscation of land is justified by the enormous debts accumulated by farmers.

In a statement published on the Telegram channel of the administration, local officials reported that farms in the district owed 40 billion soms ($3.2 million) in taxes and 128 billion soms ($10 million) to banks, and hundreds of cases are under review. The authorities also confirmed that they have filed lawsuits to terminate lease agreements with at least 110 farms.

Farmers and analysts note that the statement does not specify how these debts arose and what role local authorities and agricultural associations played in this.

Regional agricultural associations in Uzbekistan are state-controlled and closely linked to local authorities.

Economist Otobek Bakirov argues that the agricultural system itself drives farmers into debt.

In an interview with Ozodlik, he stated that many farmers in the harvest seasons of 2024 and 2025 “did not receive full payment from cotton and grain clusters” from regional associations, leading to delays in fertilizer supplies and, consequently, reduced yields.

“Most farmers ended up in debt,” Bakirov explains.

Local authorities assure that allocating more agricultural land to foreign investors will contribute to economic growth. However, the implementation of these plans typically leads to the displacement of local farmers. People in rural areas often have no other sources of income.

The loss of approximately 300 farms in the Khavast district could leave thousands of families without livelihoods, according to local farmers.

“Farmers are leaving, workers are leaving, villages are emptying,” says one local resident. “Migration is increasing. Investors come and go, and we are left with nothing.”

As discontent grows in the Khavast district, the government in Tashkent has begun to show signs of political resistance.

Deputies of the Liberal Democratic Party of Uzbekistan sent an official request to Turdimov demanding explanations regarding the situation with farmers in the Khavast district.

No response has yet been received from the hokim.