Deforestation Forces Mosquitoes to Switch to Human Blood

This shift significantly increases the risk of spreading dangerous viruses such as dengue and Zika.

As the area of the Atlantic Forest decreases, mosquitoes are increasingly turning to humans as their primary food source. This change could accelerate the transmission of insect-borne diseases and make communities near the forest more susceptible to disease outbreaks.

The Atlantic Forest, stretching along the coast of Brazil, is renowned for its vast biodiversity, including numerous species of birds, mammals, amphibians, and reptiles. However, much of this diversity has already been lost, and human activity has reduced the forest to one-third of its original size.

With the encroachment of humans into previously untouched ecosystems, wildlife is being displaced, and mosquitoes that once fed on a variety of animals are now switching to humans, as indicated by the study published in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution.

“We demonstrated that mosquitoes caught in the remnants of the Atlantic Forest clearly prefer human blood,” noted Dr. Jeronimo Alencar, the lead author of the study and a biologist at the Oswaldo Cruz Institute in Rio de Janeiro.

“This has serious implications, as in ecosystems like the Atlantic Forest, with a large number of potential hosts, a preference for humans significantly increases the risk of pathogen transmission,” added co-author Dr. Sergio Machado, a microbiology and immunology researcher at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro.

To determine what mosquitoes are feeding on, the research team set up light traps in the reserves of Sitio Recanto and the Guapiacu River in the state of Rio de Janeiro. The researchers separated female mosquitoes that had recently fed on blood for further analysis in the laboratory.

The scientists extracted DNA from the blood samples and sequenced a specific gene that serves as a biological barcode. Each vertebrate species has a unique version of this genetic marker. By matching the barcodes with reference databases, the team was able to identify which animals had fallen victim to the mosquitoes.

The traps collected 1,714 mosquitoes of 52 different species. Blood was found in 145 females, and the researchers were able to identify the blood sources in 24 individuals, which included 18 humans, one amphibian, six birds, one member of the canid family, and one mouse.

Some mosquitoes fed on the blood of more than one host. For example, one mosquito identified as Cq. venezuelensis took blood from both a human and an amphibian. Mosquitoes of the species Cq. fasciolata also exhibited diverse feeding habits, including combinations of rodent and bird blood, as well as bird and human blood.

The researchers believe that such changes in mosquito behavior may be driven by multiple factors. “Mosquito behavior is quite complex,” noted Alencar. “While some species may have innate preferences, the availability and proximity of hosts play a crucial role.”

With ongoing deforestation and the expansion of human settlements, many species of plants and animals are disappearing. Mosquitoes are adapting to these changes by altering their habitats and foraging methods, often moving closer to humans.

Mosquito bites pose a serious health threat. In the studied regions, mosquitoes transmit viruses such as yellow fever, dengue, Zika, Mayaro, Sabia, and chikungunya, which can lead to long-term consequences. Scientists emphasize that understanding mosquito feeding preferences is crucial for studying disease transmission in ecosystems and among populations.

Additionally, the study revealed data gaps: less than seven percent of the captured mosquitoes had traces of blood, and sources could only be identified in 38 percent of cases. This highlights the need for more in-depth and large-scale studies, including advanced methods for detecting mixed blood sources.

Nevertheless, the findings have practical significance. They could contribute to the development of effective measures for controlling mosquito populations and improving early warning systems for disease outbreaks.

“By knowing the preferences of mosquitoes in certain areas, we can proactively warn about the risk of infection transmission,” concluded Machado.

“This will allow for targeted monitoring and preventive measures,” added Alencar. “In the long term, this could lead to the creation of control strategies that take into account the balance of the ecosystem.”

Read also:

IAEA and Graz Announce Results of Mosquito Sterilization Experiment

Photo IAEA. The impact of climate change on mosquito reproduction The first results of the...

Mexico bans the use of dolphins, whales, and other marine mammals for entertainment purposes

The Senate of Mexico has completed a three-year legislative initiative, unanimously approving a...

Results of the Experiment on Mosquito Sterilization Using Radiation Are Presented

According to information provided by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and the city of...

Problems of Diagnosing Hip Joint Dysplasia in Kyrgyzstan. Archival Interview with Kasymbek Tazabekov

In Kyrgyzstan, orthopedic diseases remain one of the key medical problems. According to the...

Aeon: How the Conquest of Foreign Territories Came to Be Considered Unacceptable

Author: Cary Goettlich In the modern world, there are fewer and fewer things that evoke consensus...

Non-Combat and Unrecognized: Suicides in the Ukrainian Army That Are Silent

This is a translation of an article from the Ukrainian service of the BBC. The original is...

Why Tourists Need Almaty, Not New York, Moscow, or Paris

Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, in an interview, emphasized the need to transform Almaty into a unique...

Financial Nihilism: Why Young People Are More Likely to Risk Money

Against the backdrop of this financial paradox, young people who cannot afford housing are...

Is Kazakhstan Awaiting a Water Collapse Following the Iranian Scenario?

The inability of the new Ministry of Water Resources to address the water shortage problem is...

The head of the White House staff stated that her sharp comments about Musk and Vance were taken out of context.

On December 16, Vanity Fair published the first part of an extensive article based on numerous...

The J-1 Cultural Exchange Program in the USA has turned into a scheme for profiting from and exploiting foreign interns, - The New York Times

Another scheme involved employing close relatives of the CEO, which brought his family over 1...

Voting - a right or a duty? The controversial bill of the deputy

Deputy Marlen Mamataliyev has proposed making participation of citizens of Kyrgyzstan in elections...

The President of Chile is José Antonio Kast, a supporter of dictator Pinochet

José Antonio Kast, representing the far-right political force, has been elected as the President...

"War Will Change Beyond Recognition." Colonel of the General Staff of Russia — on the Lessons of Military Actions in Ukraine, Changes in the Army, and the Weapons of the Future

The conflict in Ukraine has not only become a catalyst for changes in the military sphere but has...

Tokayev: Kazakhstan has entered a new stage of modernization

Curl error: Operation timed out after 120001 milliseconds with 0 bytes received...

Historic Agreement on Ocean Protection Takes Effect Today

Today, an important document officially comes into effect — the Agreement on the Conservation and...

US sanctions kill half a million people a year worldwide

In a study conducted by scientists from the University of Denver and the Center for Economic...

Russian and Ukrainian Drone Manufacturers Buy Components from the Same Chinese Companies

According to The Financial Times, Russian and Ukrainian drone manufacturers are using the same...

Life in the Regions: Nature Became a Source of Inspiration for Artist Süünbek Rahimduulaev from Karakol

Suyunbek Rakhimdulaev, a creative resident of Karakol, has been passionate about painting for many...

Like Another Planet. A Kyrgyz Person on Life in Papua New Guinea and Working at the UN

Kанагат Алышбаев, a native of the village of Sary-Kamysh in the Issyk-Kul region, holds a degree...

Fatty cheeses and creams are associated with a lower risk of dementia

According to a conducted study, participants who consumed at least two slices of fatty cheese...

Kyrgyzstanis Mostly Work Informally. What Reforms Could Change the Situation?

In 2025, the International Monetary Fund presented an analytical report on the state of the labor...

Cinema as a Tool for Human Rights Protection: An Interview with Swiss Documentarian Stefan Ziegler

At the end of 2025, a ceremony for the "Ak Ilbirs" award took place at the National Opera...

Study: Over 20% of Videos Shown on YouTube Are "Low-Quality Content Created with AI"

According to the findings of the study, low-quality AI-generated content is becoming increasingly...

Nelly Nosalik: Advertising on Social Media - The Most Promising Direction

In Kyrgyzstan, there is a growing interest in women's entrepreneurship in the field of...

Chinese investors established 500 million cubic meters of gas reserves — what is known about the field in Batken

The Kadamjai district has still not determined the gas reserves that are surfacing. About ten...

Nostradamus' Prophecies for 2026: King Donald Trump, the Decline of the West, Widespread War, and AI

As 2026 approaches, interest in Nostradamus' "Prophecies" — the famous collection...

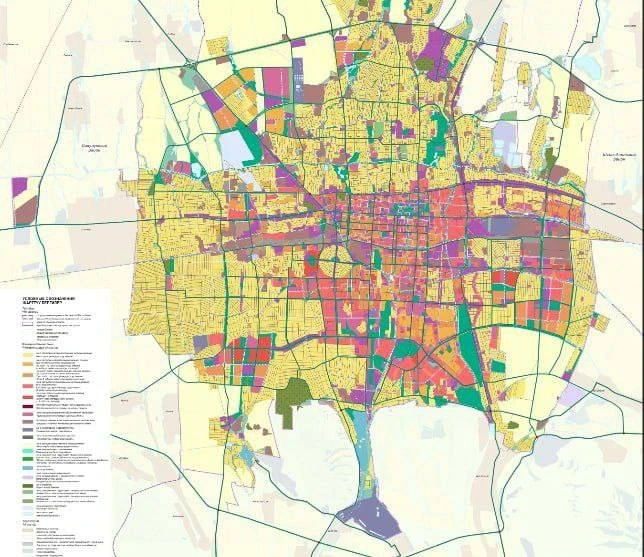

Bishkek Master Plan: Whose Homes and Lands May Be at Risk of Changes

The Bishkek City Hall presented responses to questions and suggestions from residents that were...

What is happening with green cards? Should we expect the lottery? And what about those who have already won it?

The U.S. Green Card Lottery (Diversity Visa Lottery) has long served as one of the most accessible...

The number of pheasants is increasing in the Issyk-Kul region

In the Issyk-Kul region, there is a positive trend in the increase of pheasant populations, which...

"Sometimes Harsh, but Necessary". How Entrepreneurs Assess the Year 2025

According to the analytical forecast of the Central Bank, it is expected that by the end of 2025,...

Zelensky spoke about the 20 points of the peace plan. What's new in it?

President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelensky presented a draft agreement for ending the war, which was...

Study: People Who Stop Weight Loss Injections Gain Weight Four Times Faster Than Those Who Were on a Diet

According to new data published in the British Medical Journal, people using injections for weight...

UN Report: 30 Times More Money is Spent on Destruction of Nature than on Its Protection

According to a new report from the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), investments...

In Bishkek, the country's water and energy security was discussed

The topic of water security in Kyrgyzstan, the resilience of mountain ecosystems, and climate...

Invisible Threat: How Polluted Air Can Affect the Nervous System. Research Findings

According to a new study conducted by scientists from the Karolinska Institute in Sweden, prolonged...

"Only the political will of the president will save the architectural masterpieces of Bishkek"

The honored architect of the Kyrgyz SSR and candidate of architecture Ishenbay Kadyrbekov recently...

How "Eurasia" is Changing the Daily Lives of Millions in Kyrgyzstan

Curl error: Operation timed out after 120001 milliseconds with 0 bytes received...

The New York Times: The Melting of Greenland's Ice Has Climate, Economic, and Geopolitical Consequences for the Entire World

The situation in Greenland affects the interests of billions of people around the world. The...

Unusual Predators Shot Near the Border of Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan

Unusual jackals were shot at the border of Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. One of the sport hunters...

Alinur had measles at six months old. Complication - a rare brain disease

Seven-year-old Alinur has been battling subacute sclerosing panencephalitis for two years—a rare...

How Crypto Miners Stole $700 Million from People, Often Using Old Proven Methods

The theft of cryptocurrency evokes a particular, agonizing feeling. All transactions are recorded...

A bird with a wingspan of up to 2.5 meters was filmed in the Talas mountains

On the territory of the Besh-Tash Nature Park in the Talas region, a rare black vulture, known to...

Fox News: Experts Assess the Impact of "Sober January" on Health

The American television channel Fox News presented an analysis of the popular trend Dry January and...

Sadyr Japarov spoke at the IV People's Kurultai (text of the speech)

Today, December 25, the President of Kyrgyzstan, Sadyr Japarov, addressed the people, the deputies...

Rasul Sultangaziev: We Always Remember the Main Commandment of the God of Medicine – Do No Harm

- The success of any surgical intervention depends on the correct medical indications, the...

UFC Fighters Coach: How Tynchtykbek Omurzakov Trains Athletes. Interview

Tynchtykbek Omurzakov is a coach who has opened the way for many mixed martial arts fighters from...

Mongols and Indians — Blood Brothers

The connection between Mongols and Native Americans is not limited to genetics but also...