Willpower and self-control are not depleted like muscles. It all comes down to brain functions.

According to a common belief, every act of self-control requires an expenditure of internal energy. For example, if you refuse dessert, it will be harder to resist the temptation to watch TV in the evening. This concept is called ego depletion and suggests that self-control drains your internal resources. This approach is intuitively understandable and helps explain why it can be difficult to resist temptations after a long workday.

What if this is not the case? What if willpower is not depleted at all?

The idea of ego depletion emerged in the late 1990s and quickly gained popularity. It was based on numerous studies showing that acts of self-control require the use of the same limited resource. When this resource is depleted, we become more impulsive and less able to control our actions.

This concept was reflected in various bestsellers and corporate training sessions; even former U.S. President Barack Obama mentioned that he wears the same suits to save energy for more important decisions. This idea proved useful, as it helped explain the state of mental exhaustion and develop strategies to strengthen willpower.

However, further research raised questions about the reliability of this theory. In experiments testing ego depletion, participants often performed one task requiring self-control and then moved on to a more challenging one. According to the theory, their performance should have declined, but meta-analyses failed to confirm this. Even attempts to replicate the results in laboratories around the world showed ambiguous outcomes.

Despite this, proponents of the theory continued to assert that the lack of task complexity was the reason for these results. Therefore, my colleagues and I developed a new model, suggesting that willpower is indeed similar to a muscle: the longer a person performs a challenging task, the more fatigued they should become.

In our 35-minute study, participants completed two tasks: the first was a complex numerical version of the Stroop test, and the second was a global-local task. We wanted to determine whether participants' ability to concentrate deteriorated over time.

Contrary to the expectations of the ego depletion theory, participants adapted during the tasks, demonstrating improvements in speed and accuracy rather than declines in performance.

It is important to note that the complexity of the test varied: some participants completed a more complex version, while others completed a simpler one. If willpower truly functioned like a muscle, then complex tasks should have led to faster depletion. However, instead, participants with more complex tasks maintained their pace and sometimes even accelerated.

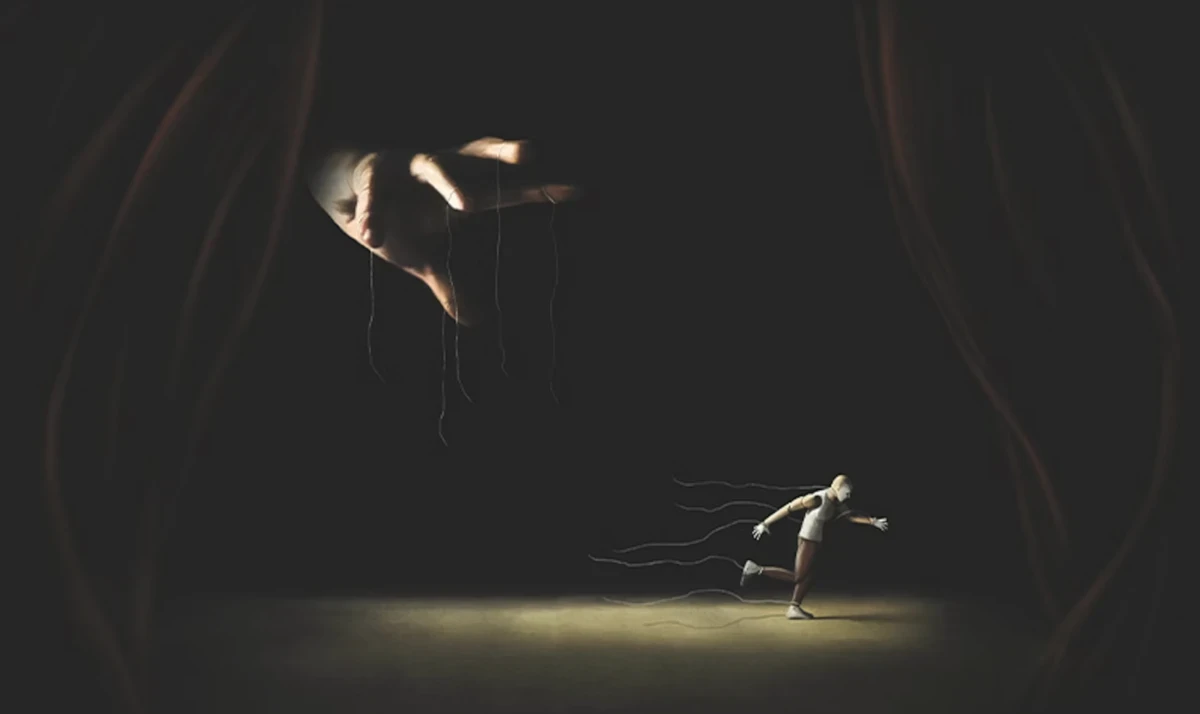

If the ego depletion theory does not reflect the reality of self-control, then it is necessary to consider another concept. One possible alternative is the metacontrol theory proposed by cognitive psychologist Bernhard Hommel. This theory suggests that the brain operates on a continuum between two states: persistence and flexibility. Persistence can be compared to a low gear in a car, while flexibility is akin to a high gear for adapting to a new situation.

When the brain is in a state of persistence, it focuses on the task and is resistant to distractions. In a state of flexibility, we are open to new ideas and better able to cope with unexpected challenges. Both modes have their advantages depending on the context.

You may have noticed how your attention shifts depending on the situation: you work on a complex task in persistence mode, and then relax and switch to more flexible thinking while socializing with friends.

It is important to understand that switching between these states is a natural process. What we perceive as "exhaustion" may actually be a transition to flexibility mode, rather than a sign of a lack of willpower. This adaptive switch could have been beneficial for our ancestors in survival conditions.

The metacontrol theory better explains changes in performance and aligns with modern understandings of neurobiology, linking changes in cognitive mode with dopaminergic activity in various areas of the brain. This opens new horizons for understanding effort, self-discipline, and failures in everyday life.

The phenomenon of "slipping," when thoughts wander, may be an adaptive mode switch rather than a manifestation of weakness. If willpower is perceived as something that can be lost, it is actually more of a mode that changes depending on context and motivation.

Thus, a short break may not be a failure but an opportunity for recalibration. Sometimes, instead of persisting, it is worth giving yourself time to reset. For example, after working on a complex project, taking a short walk or switching activities can allow your brain to adapt without succumbing to burnout.

If we reject the metaphor of willpower as a muscle, we can envision it as a car that shifts gears depending on the environment and goals. This implies that understanding the processes is more important for improving willpower than mere persistence. It is necessary to develop more detailed psychological models that reflect the true mechanisms of brain function.

Source