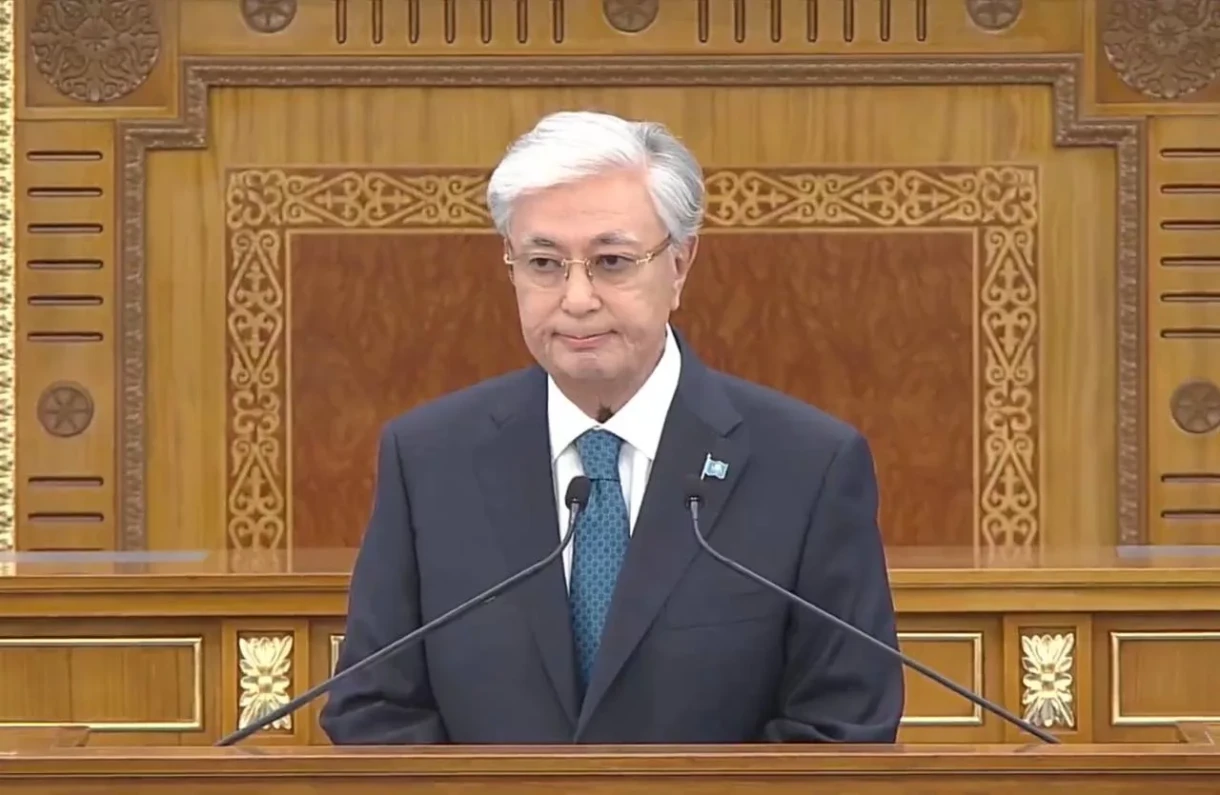

In recent months, alarming reports about an impending water resource shortage have emerged from several Central Asian countries. In his Address to the People of Kazakhstan in September 2025, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev emphasized that the issue of water scarcity in the country has reached the status of a national security concern. Kazakhstan subsequently announced an anticipated deficit of 1 billion cubic meters of irrigation water expected from spring 2026. In mid-January 2026, the Ministry of Agriculture of Kyrgyzstan warned farmers about a possible shortage of water resources in the upcoming growing season. As a result, these countries may face a water resource deficit as early as this year, as reported by the Independent Newspaper.

The factors contributing to water shortages are well-known: climate change, reduced precipitation, and the continuous population growth in Central Asian states. There is also an increase in water consumption for domestic needs, which is linked to population growth and, as a rule, irrational resource use. In 2023, the Eurasian Development Bank noted that the water supply systems in the region are outdated, leading to losses: about 40% of water is lost during irrigation and up to 55% during the supply of drinking water.

Agriculture, energy, and industry constitute a significant portion of water resource consumption. Glacial melting and agricultural waste deplete reserves, and the lack of effective water resource management can exacerbate interstate tensions. For example, Afghanistan, which has long ignored Central Asian countries in discussions about water issues, is now constructing the Kosh-Teppa canal, scheduled to be operational in 2026–2027, which will significantly impact the water resource situation in the region. The Afghan side continues to implement this project, acting in its own interests without considering the interests of its neighbors.

Despite the growing deficit, Central Asian countries are unable to change the situation. Public discussions focus on the rational use of water resources and the development of cooperation. For instance, in November 2025, Uzbekistan's President Shavkat Mirziyoyev proposed at the seventh Consultative Meeting of Central Asian Heads of State to declare 2026–2036 as a decade of practical actions for the rational use of water. He noted that for this, countries must take real steps in water policy aimed at sustainable economic development and environmental protection. However, in practice, the situation looks different. Despite statements about cooperation, countries continue to exhibit water selfishness at the national level. For example, as of January 1 of this year, a new Water Code came into effect in Kyrgyzstan, stating that water resources are considered a commodity not only for domestic but also for external consumers.

The implementation of water-saving policies also faces challenges. Transitioning to water-saving technologies and cultivating less water-intensive crops requires significant financial investments. However, the funding necessary for implementing such technologies has become a serious problem for the countries in the region. In 2025, the Eurasian Development Bank noted that funding in Tajikistan over the next five years would not meet the population's needs for clean drinking water. It is expected that $0.4 billion will be invested in the country from 2025 to 2030, while needs are estimated at $1.7 billion. A similar situation is observed in other countries in the region.

While the leaders of Central Asian countries discuss water issues and make pessimistic forecasts, reality continues to deteriorate. In several Central Asian countries, conclusions have already been drawn about the negative impact of water resource shortages on economic development and the social sphere. The President of Uzbekistan emphasized that annual losses due to moisture shortages amount to about $5 billion, and in the coming years, the water deficit could reach 25–30% of needs. This scenario could adversely affect not only the development of individual countries but also interstate relations in Central Asia.

The water deficit in Central Asia has become chronic. Although warnings about potential conflicts between states over water resources are becoming more frequent, the problem remains unresolved. In January of this year, a report from the United Nations University Institute for Water, Environment and Health stated that the world has entered an era of global water bankruptcy: "The world has entered an era of global water bankruptcy, where critical water systems have suffered irreversible damage and can no longer meet the growing needs of humanity." According to the Eurasian Development Bank, acute water shortages in Central Asia could arise as early as 2028.

This study examines the causes of water problems and conflicts in detail, but the main conclusion is simple: there is less water. This has led to the destruction of approximately 410 million hectares of natural wetlands over the past 50 years. Although Central Asia has not yet reached the critical level of water scarcity that threatened Cape Town in 2018, the direction of events is clear. Without decisive measures to modernize water infrastructure and jointly manage the region's rivers, megacities such as Tashkent, Bishkek, Almaty, Astana, and Dushanbe may face an irreversible crisis.

In recent years, there have been numerous scenarios for the development of the situation in Central Asia against the backdrop of increasing water resource shortages. All of them converge on the point that water scarcity will lead to population migration both within and beyond national borders, ultimately contributing to interstate conflicts in the region.