In Kyrgyzstan, a similar position existed in the early 1990s but lasted for a short time. The editorial team of Kaktus.media recalls the events that led to its abolition and subsequent attempts to revive this institution.

The Vice-Presidency in Kyrgyzstan in the 1990s

The position of vice-president was established in December 1990, during changes in the government as part of the overall restructuring. The first vice-president of the Kyrgyz SSR was Nasirdin Isanov, who came in second in the first presidential elections of 1990 after Askar Akayev. However, on January 21, 1991, he was appointed chairman of the Council of Ministers and continued to lead the government after independence, becoming the first prime minister of the new Kyrgyzstan.The vice-presidency in the 1990s was conceived as a deputy to the president and a potential successor, similar to the American model. But in reality, its powers were unclear and poorly defined. He had no specific area of responsibility and was neither the head of government nor the speaker of parliament, which reduced his role to symbolic tasks. For example, German Kuznitsyev dealt with economic issues but had no influence on strategic decisions.

The main risk was that the presence of an official "heir" was perceived as a threat to the president. This situation could provoke rivalry among elites for support of the vice-president. Examples from post-Soviet history show that under such conditions, the vice-president can become a source of conflict. In Kyrgyzstan, there were no such conflicts, but the concept of "dual legitimacy" made the institution vulnerable. As a result, in 1993, the vice-presidency was abolished as part of the strengthening presidential vertical.

Discussion of the Vice-Presidency in the Future

Since 1993, Kyrgyzstan has long avoided the return of the vice-presidency. Neither Askar Akayev nor his successors supported this idea, likely due to a reluctance to create potential competitors. However, from time to time, various politicians and experts expressed thoughts about the return of the vice-presidency under new conditions.The first instance when the topic of a second state figure was raised again occurred after the "Tulip Revolution" in 2005. At that time, an informal tandem formed between Kurmanbek Bakiev and Felix Kulov, which indeed contributed to stabilization. But this alliance quickly fell apart due to internal disagreements. In 2011, public figure Rasul Umbetaliev, analyzing past events, proposed creating the vice-presidency at an institutional level to avoid informal agreements. He believed that the vice-president should have real powers and legitimacy from the people, suggesting that the position could be occupied by the candidate who came in second in elections, reminiscent of the American practice of the 18th century. However, in 2011, this initiative remained at the discussion level.

Discussion about the vice-presidency resumed at the end of 2020, when, after the events of October and the coming to power of Sadyr Japarov, the question of a new constitution arose, which returned Kyrgyzstan to a strong presidential model. At the constitutional meeting, it was proposed to establish the vice-presidency to take into account regional interests. Syrgak Kadyraliev, an associate professor at AUCA, emphasized that such a model could help in national unity. However, many members of the meeting viewed this proposal skeptically, preferring to focus on other aspects of the reform. As a result, the new constitution adopted in 2021 did not include the vice-presidency, retaining the traditional scheme with the head of parliament as the "first deputy" of the president.

Throughout independence, ideas about the vice-presidency have mostly been raised during political crises or reforms, but none have been implemented, partly due to the fear of repeating the negative experience of the 1990s, when the lack of clear rules turned this position into a source of conflict.

Global Experience of the Vice-Presidency

The vice-presidency has a primary function — to ensure continuity of power and avoid a legal vacuum in the event of an unexpected resignation, death, or incapacitation of the president. In countries where this model operates, the "second person" assumes their powers without delays or political disputes, following established constitutional procedures.A classic example is the USA, where the vice-presidency is considered an element of stability. The vice-president in the USA not only holds the second position in the executive branch but also plays an important role in the legislative process, presiding over the Senate and having a decisive vote in the event of a tie. This structure ensures both continuity and participation of the second person in current governance.

In Latin America and other regions, the principle is also oriented towards continuity of the course chosen by voters. For example, in Brazil, twice in history, newly elected presidents died before taking office, and the vice-president automatically became president, which helped maintain the legitimacy of the elections and avoid a governance crisis.

There are also other models where the vice-presidency is introduced as part of a power reform. For instance, in 2018, Turkey abolished the position of prime minister and introduced the vice-presidency under conditions of strong presidential power, which effectively became a variant of the classic presidential system.

However, the vice-presidency can also create potential conflicts. Critics point to the risks of duplication and rivalry. If both the prime minister and vice-president positions exist simultaneously, this can lead to conflicts of interest, especially in conditions of weak party discipline.

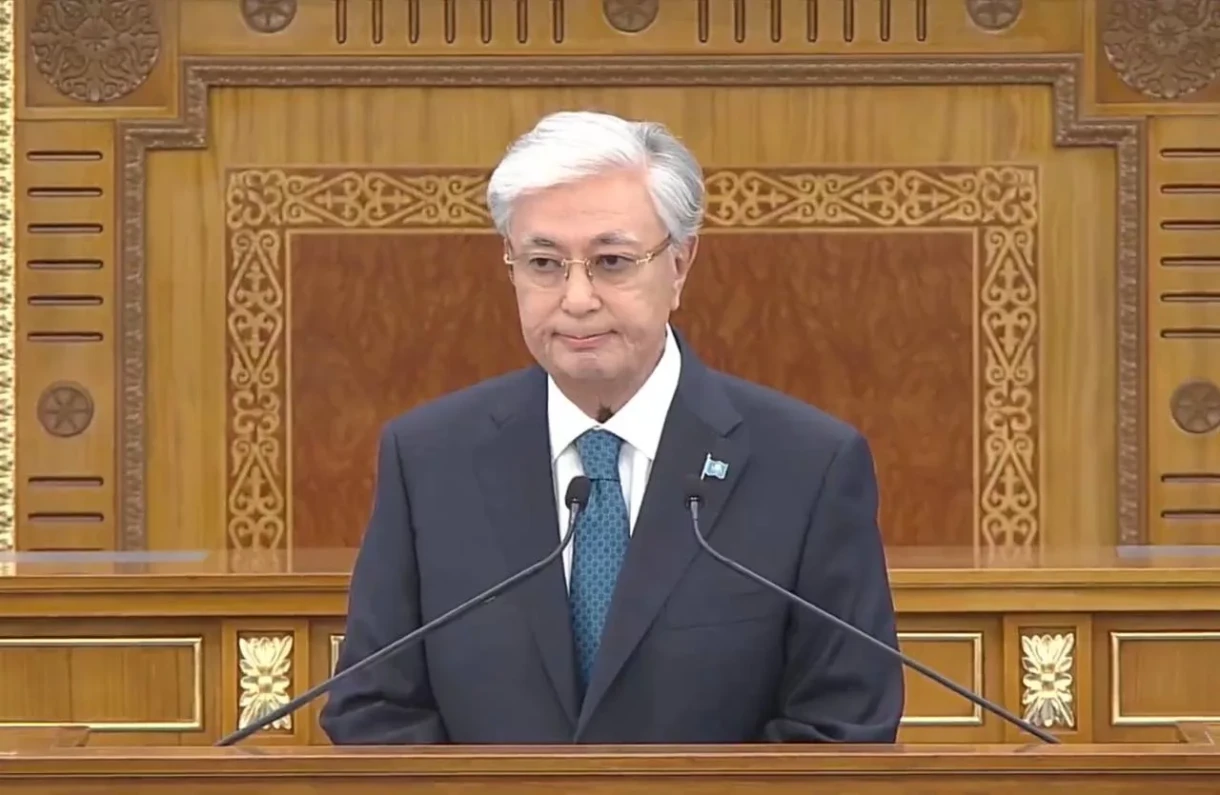

Post-Soviet experience confirms these risks. Erik Asanbayev, the only vice-president of Kazakhstan, later acknowledged that the "president – vice-president – prime minister" model proved ineffective due to blurred boundaries of powers and conflicts, instead of the desired stability.

Another systemic risk is related to the "heir problem." If the constitution clearly states who becomes president in the event of an early resignation, this can create a temptation for some elites to rely on the "second" as an alternative source of legitimacy in crisis situations. Examples from post-Soviet history, such as Yanayev in the USSR and Rutskoy in Russia, demonstrate that the vice-president can become not a "safety net," but a center of political confrontation.

It is also worth considering the architecture of the executive power and which positions may be abolished to prevent bureaucratic growth. For example, in Kazakhstan, there are plans to simultaneously abolish the institution of the presidential state advisor.

A more radical approach could involve merging the positions of vice-president and prime minister, simplifying the hierarchy: president, his deputy (heading the cabinet of ministers), and speaker of parliament. This would require a transition to a model where the government is directly dependent on the president and his deputy.

In some countries, the vice-presidency is used not to ensure stability but to strengthen personal power. In 2017, Azerbaijan introduced the position of first vice-president, occupied by the wife of President Ilham Aliyev, which effectively solidified dynastic power transfer.