With the beginning of the growing season in 2026, Kyrgyzstan is once again facing alarming news. The Ministry of Water Resources, Agriculture, and Processing Industry of the republic is reporting a water shortage, emphasizing that this is not their fault but a consequence of natural factors. In this situation, a reasonable question arises: if the agency has been aware of glacier melting and global warming for many years, why are its actions limited to merely stating the facts rather than moving towards active measures to address the problem?

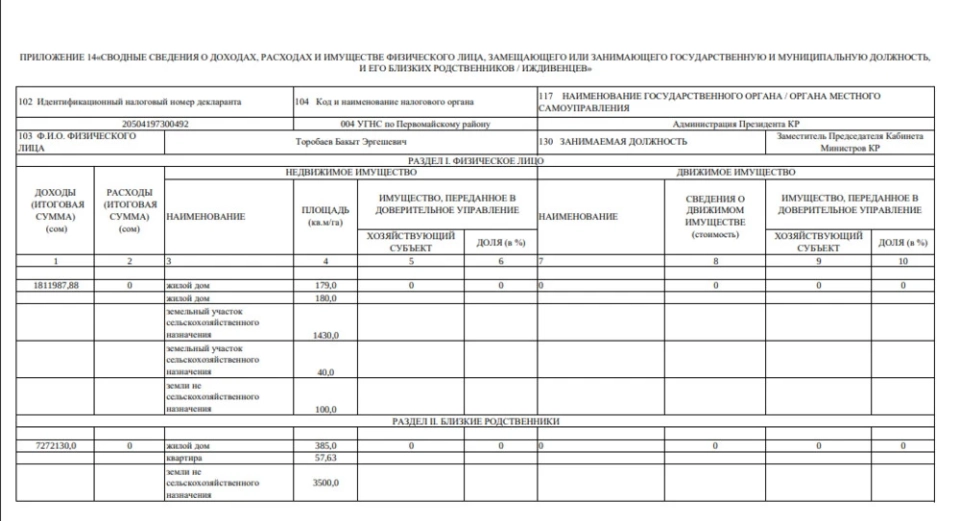

It should not be forgotten that back in May of last year, Minister Bakyt Torobaev appealed to farmers to use water resources rationally. He emphasized that in conditions of abnormal heat, every drop counts, and the country's success depends on the ability to use water efficiently. Torobaev assured that the implementation of water-saving practices by farmers would help avoid shortages. However, a year later, we are hearing the same calls again. If the minister's primary task is merely to persuade farmers to save water, one can doubt the effectiveness of his management.

Nevertheless, behind these correct words lies a harsh reality. The ministry constantly reports on the allocation of preferential loans for the installation of drip irrigation systems, yet in practice, this process proves to be difficult. As farmers have explained, they are ready to transition to modern technologies, but bureaucratic hurdles and strict collateral requirements create barriers that not everyone can overcome. As a result, innovations remain only on paper, and fields remain without water.

Perhaps, to resolve the current situation, it is worth studying the experiences of other countries more closely. Although the agency is likely already familiar with these examples, the issue probably lies in their implementation. For instance, in Israel, where more than 60% of the territory is desert, the country successfully engages in agro-export. If the Israelis saw our fertile lands, they would probably laugh at our "drought." The Israeli model could serve as a handbook for Torobaev if he truly wants to develop agriculture. Here are a few aspects from the Israeli experience:

- recycling 95% of wastewater: Israel cleans and reuses water twice.

- dominance of drip irrigation: in Israel, this is not just a recommendation but a standard. Each plant receives water through systems managed by sensors and artificial intelligence.

- smart technologies in agribusiness: Israel offers the world knowledge and precision agriculture technologies, successfully growing tomatoes, strawberries, and flowers in the desert with minimal costs.

In conclusion, it can be said that the effectiveness of officials' work, particularly the minister's, should today be assessed not by frequent trips across the country or the opening of small agricultural enterprises, but by the number of hectares that meet Israeli water use standards. A simple appeal to farmers to save water could turn the agency into a "ministry of drought," which merely records losses in the agricultural sector.

It is likely that 2026 will be a decisive moment for Kyrgyzstan. Either the Ministry of Agriculture under Torobaev's leadership will ensure technological progress and make modern irrigation systems accessible to every farmer, or it will acknowledge its incompetence. Either we create Israel in Central Asia, or we prepare for our fields to turn into desert.